The great globe itself

Sometimes we have these outbursts in my corner of the media world. The past few weeks, it’s been about the new “podcast” category of the Golden Globes. The winner, announced January 12, was a popular video-chat show. But the outburst concerned the fact that almost all the finalists were also video-chat shows.

“They are identical in form: the host(s) and guest(s) spend around an hour congratulating each other on their kindness, funniness and general wonderfulness,” complained The Economist.

“If we want high-quality, narrative-driven audio to survive…if we want podcasts that aren’t just celebrity chat shows with cameras, we have to reward them for existing. Awards matter. Recognition matters,” declared Jacob Reed.

The New York Times also ran an op-ed. This all seems like a lot of media attention for a seemingly minor issue while all around us rage protests, protests, protests, siege and protests. The point is, though, that podcasts also cover things like siege and protest, but Hollywood is now using its flattening powers to brand the form as just light gabbing.

The Golden Globes are never going to be The Peabodies. Professional anxieties fueled the controversy — anxieties that streaming video platforms have redefined, if not partially obliterated, the imaginative world of listening. Critics complain video dominance is already making audio sound bad. Long-time readers of Continuous Wave recognize the historical pattern here and already know how US networks made a Faustian bargain with TV in the early 1950s, after which radio emerged as a weakened and entirely different form.

Is that what’s going on today, another Faustian thing? If so, the Devil is getting a bargain. And anyway, why won’t these two forms, audio and video, be content to live side by side and serve the complementary audiences who love each one? Of course, the answer is about money, sure — but I think there’s something else at play, something unperceived. Not surprisingly, I also think that old books can shed a useful light on that.

So what follows is deep cut on video versus audio. Bear with me as I try a theory out on you. It’s the theory of magic versus circus.

Magic becomes media

My best friend (to my mind — he is dead and we’ve never met) Erik Barnouw started in radio in the 1930s as an ad-agency scriptwriter. Later he became a professor, media historian and filmmaker. But his very first job as a teenager was to catalogue the library of the magician John Mulholland. And Barnouw’s 1981 book The Magician and the Cinema applies his experience with magical lore to modern media.

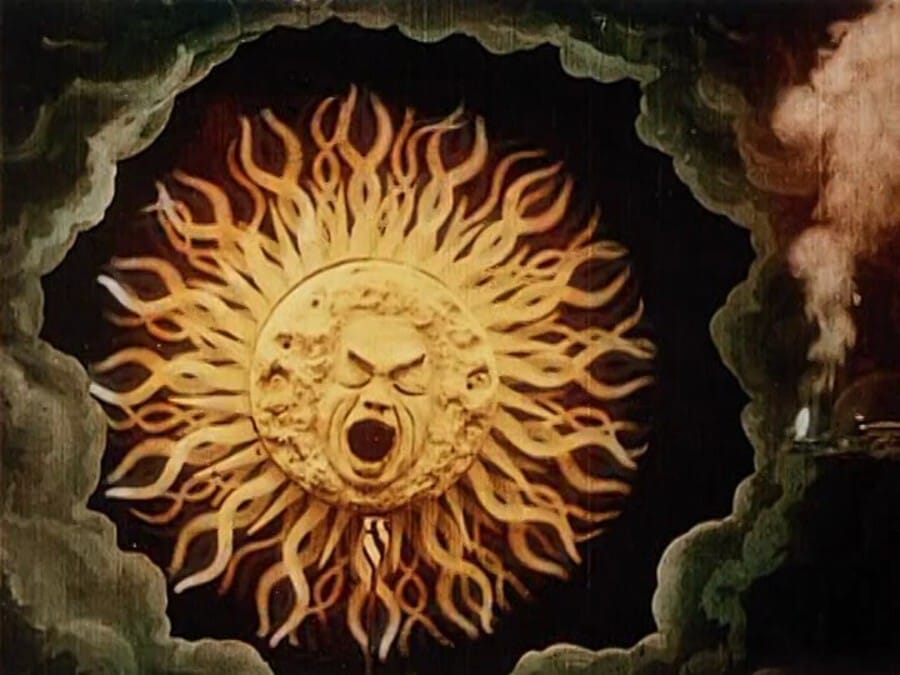

Barnouw argues that movies, in particular, owe their existence to magic shows. As early as the 1790s, magicians were using tricks with light, projection and, yes, smoke and mirrors, to create the machinery of illusion that led directly to the development of cinema.

Nineteenth-century magicians brought to their profession a zestful appetite for science. Most were grounded in ancient varieties of legerdemain, and combined them with such specialties as juggling, escapology, shadowgraphy, chalk-talk, ventriloquism, mind-reading or instant-transformation acts. But they also found, in that century of prolific invention, that every new scientific invention had magic possibilities. The magician made it his business to stay a step or two ahead of public understanding of science. New tricks came as fast as inventions. By their very nature, many of these tricks had a short life, as public understanding caught up with them.

But then, the popularity of film escaped their control. “The transfer to the screen of the magician’s most sensational illusions — disappearances, bizarre transformations and beheadings — proved ultimately catastrophic for magicians,” Barnouw writes, pointing to the financial ruin of French “trick film” magician George Méliès. “The magician found he had been helping to destroy his own profession.”

Once you start looking for the legacy of the magic show in modern media, you see it everywhere. But that legacy resides in the recorded arts. Recordings are, when you get down to it, a type of magic trick — and often presented to the public first on that basis.

In his book Perfecting Sound Forever, Greg Milner evokes the Edison Company “tone tests” of the 1910s and 1920s. These were popular demonstrations of recorded music. A singer would stand before a live audience and accompany a recording of herself after the lights went down. The audience would try to judge if they could hear a difference. Generally they could not, to their astonishment — but subtle trickery was involved. The singers on Edison’s roster had learned to flatten their tonal range to match the recording’s. Milner says it was preternaturally smart of Thomas Edison to latch onto “authenticity” as a selling point for his wax cylinders, because that assumption is now imbued in every recorded song we hear.

Today, special effects dazzle us, but they don’t really fool us; we may not know exactly what makes the Death Star blow up, but we know there is no Death Star. Recordings, on the other hand, must trick us to work, and always ask that we suspend our disbelief. We are supposed to hear the sound of Led Zeppelin jamming together in real time. The narrative of a film might jump around in time, but a song is always linear. We’re not supposed to hear the sutures. A recording is nothing until it is decoded, and what it decodes is always an illusion.

At the same time that tone tests, movies and magic shows were roaming the land in search of dollars, another popular entertainment was raking them in: The traveling circus.

A big production

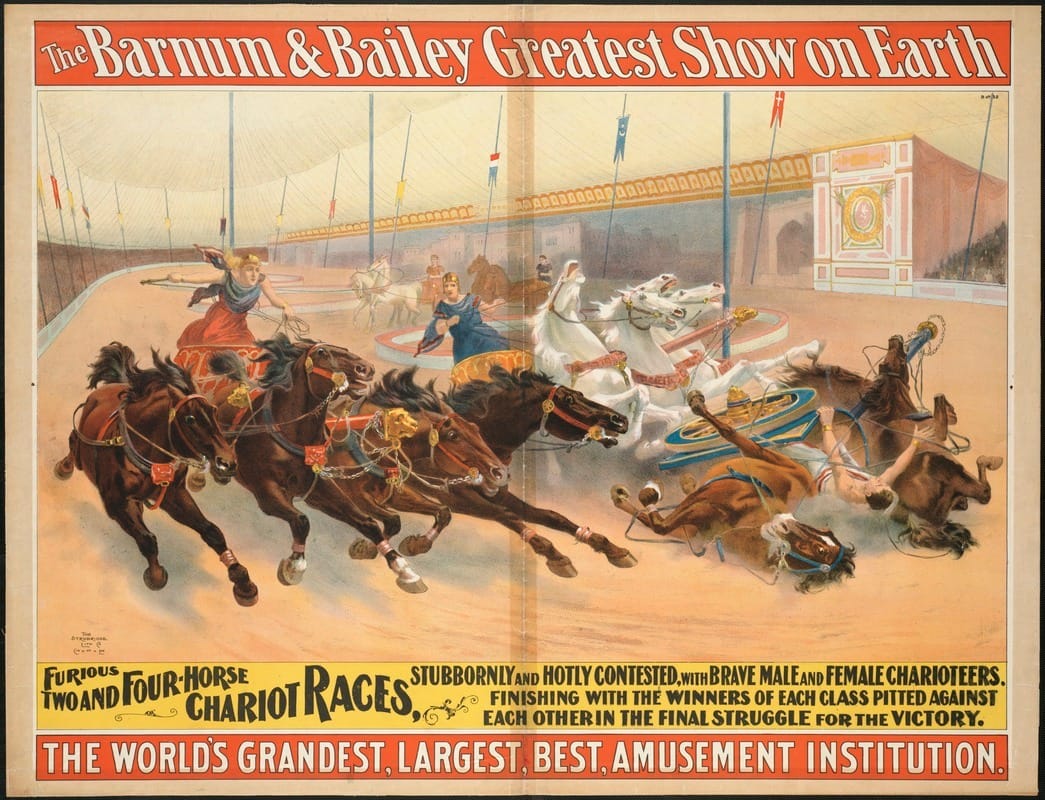

The circus is much less about fooling your perceptions than grabbing your heart. You watch in semi-terror as a rider stands on their hands atop a galloping horse, or as an acrobat spins high in the air, held aloft only by the grip of their teeth on a stirrup. Even if the performers rehearse relentlessly and have skilled techniques, the risks they take every day are real — and have to be for the show’s appeal to work.

Network broadcast production resembled the circus because it was both continuous and live. Both entertainments required stringent planning and execution. Circus historian Mark St. Leon described what it took to pull off a “big top” show of the type popular in the 1920s, right around the same time that radio was getting its start.

There were three rings and two stages and these were worked almost continuously throughout the two-and-a-half-hour program. No act was allowed more than five minutes…and there was not a second’s delay from the time the big parade took place around the hippodrome track that surrounded the three rings until the final chariot race.

For some personalities in early radio, the big top was not just metaphor — it was job history. Estella Karn, the longtime show runner for host Mary Margaret McBride, had actually run away from home in her youth and joined the circus (as an advance press agent, the person who rode ahead of the show to plaster the next town with posters and ads to drum up ticket sales).

When Karn first met McBride in the early 1920s, the two would go together to the offices of Billboard magazine, which at the time had a mail service for traveling performers. “I met snake charmers, sword swallowers, fire-eaters, operators of shooting galleries and weighing concessions as well as mellow-voiced spielers,” McBride wrote years later.

McBride was a print journalist who broke into radio in 1934 on a WOR midday show intended for housewives. She persuaded the station to hire Stella Karn, who knew that radio was show business, and that show business involved risk and spectacle. It was Karn who suggested that McBride try an ad-libbed interview format, which almost no one on air dared to do in those days, for fear that guests would either blow through the time restrictions or say something inappropriate.

But the sound of people talking normally, even confessing their secrets, proved irresistible. Karn had bigger plans: for McBride’s tenth anniversary on air, she booked the occasional circus venue Madison Square Garden, and the show promptly sold out. For the 15th anniversary, they broadcast live from Yankee Stadium. On both occasions, Stella Karn wanted her host to ride in on an elephant, but she refused.

McBride wrote that one time a comedy duo tried to bring a trained bear into the studio, but the minute Stella Karn saw it, she commanded it to leave. She then punched it on the nose to defend her host. In 1962, when Readers Digest printed McBride’s retrospective on Karn, that was the moment they wanted to illustrate.

Did this actually happen? We’ll never know.

While generally lacking in animal abuse, broadcast radio did owe much of its cultural impact to moments of disaster and risk, from live prize fights to exploding airships. Even literary playwrights took advantage of the suspense built into live performance. Radio historian Neil Verma hears it in the work of Norman Corwin, whose scripts challenged actors and required a virtuoso read.

The key to the Corwinesque was to be seen to be walking a high literary wire without a net. Nothing confirmed that better than a fall. I’d wager many listened for a lousy line or overdone tune as part of the pleasure of it all, as a confirmation that the broadcast was truly experimental, breaking new ground. Moreover, the high-wire act of the Corwinesque relies on a kind of listening-for-risk that was inherent in the radio of the 1940s and is impossible for us to enter into now, because we can’t listen to Corwin’s work new, fresh, or live.

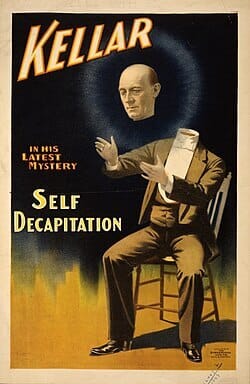

Don’t lose your head!

Pick a side?

When you apply the circus vs magic theory to modern media, you start to focus less on the delivery system than how a particular show appeals to us. As a podcast story editor, I’m definitely on Team Magic (and next week, we’ll meet someone with an even more direct connection). We editors aren’t only about removing distractions, confusion and bad facts. We want to deliver something that immerses the mind — a heightened illusion of reality, one that manages to make us forget it is all pre-recorded.

But I have to admire the honesty of the more straightforward circus spectacle. Humans are just weird. We long for stuff that excites and frightens us. The circus acknowledges that truth, and then simply delivers those feelings. Of course, circus-type motivations are not great when applied to journalism (even worse when journalism encourages you to bet on news outcomes). They vibes are even worse when they seem to consume government officials.

The appeal of the circus, however, can explain why a film-illusion shop like Netflix might want a little podcast sideshow on their platform. It’s because conversational shows are not scripted — certainly not to the level of your Stranger Things or even Tiger King. Two people talking spontaneously feels a little risqué in the airless world of streaming TV — exactly the same way it did back in the 1930s, when almost every word on the radio was read off a piece of paper.

The problem is not with either circus or magic show. The problem, as Erik Barnouw warned in The Magician and the Cinema, is that we don’t always know in our mediated world what we’re in thrall to. Barnouw thought audiences had much more skepticism about magic tricks back when they were presented as part a traveling show.

“Media images are no longer seen by the public as optical illusions offered by magicians, but as something real. The unawareness is equivalent to defenselessness,” he says.

And then he quotes Ingmar Bergman, who once wrote:

When I show a film I am guilty of deceit. I use an apparatus which is constructed to take advantage of a certain human weakness, an apparatus with which I can sway my audience in a highly emotional manner — make them laugh, scream with fright, smile, believe in fairy stories, become indignant, feel shocked, charmed, deeply moved or perhaps yawn with boredom. Thus I am either an imposter, or when the audience is willing to be taken in, a conjurer.

Unlike a sad awards show, it kind of makes you think.