Thanks to all the new subscribers coming over from Transom. I’m gratified by everyone’s interest. Special shout-out to Sound School Podcast host Rob Rosenthal, who just had me on the show along with producer extraordinaire Sarah Montague.

Note on this edition: This is the second of a mini-series on how radio got established as a live medium in the US. (Part 1 is here.) It’s probably the most academic thing I’ll post for a while. Not only is it a lot to read, it’s a lot to write — but I think these posts are important for context going forward. Still, I am by nature more attracted to shorter and quirkier stories. In fact, there are so many in radio’s archive, I need you to help me decide what to write about next. Leave a comment below if there’s something you’d like me to tackle.

Announcement in QST, a magazine devoted to wireless amateurs, May 1917.

Nab a ban

For a country so vigorously dedicated to fucking around and finding out, the story I’m going to tell — that of radio imposing a careless rule on itself, then clinging to it for way too long? It maybe doesn’t qualify as the worst chain of consequences in US history. Still it does, by the end, lead to reporters risking their lives in service of a moldy, profit-driven corporate edict.

Anyway. Let’s get into it, with some questions to guide us along the way.

Radio, as we’ve noted, started off as live, two-way communication. When it was just “wireless” and used for Morse Code signals between ships, the main problem wasn’t recording but reception — who was listening to hear distress calls? When radio amateurs joined the airwaves party and started chattering away in Morse Code, regulators got alarmed. They started to require anyone with a radio license to observe “silent periods” — fixed three-minute intervals when only distress calls could be sent and hopefully heard without interference and chatter.

This silent period became two silent years starting in 1917, as the US entered the first world war. The Navy seized control of the airwaves, banning all amateur and experimental transmissions so the military could have exclusive use of this powerful communications technology. After the war, the military tried to keep that control, but Congress refused. Instead it restored radio to the jurisdiction of a bureau within the Department of Commerce.

The Bureau of Navigation had been set up decades earlier to do very un-radio-like things such as overseeing “the collection, preservation and sale of wrecked, abandoned and derelict property” (i.e., abandoned boats). But it also inspected merchant marine vessels in US waters, which is why it was assigned jurisdiction over radio. After the war, a cacophonous din of amateur broadcasters arose even louder than before on “land stations” around the country (at first sharing a single wavelength, the equivalent of 833 on the AM dial today, but then more wavelengths as transmitting and tuning technologies improved). The technocrats within the Department of Commerce had to figure out how to handle these radio users who did not behave like ships at all. For one thing, technology improved so that people could talk via radio waves and play records. (For more, see Susan Douglas’s Listening In: Radio and the American Imagination.)

In a 1922 memo, the Bureau established a new wavelength (at 750 on the AM dial) for stations that could show they met certain professional standards. To get a coveted “Class B” license, a station’s studios needed to be sound-proofed. Their antennae needed to be solid. They needed a way for engineers to communicate with the speaker on air, and above all, they needed to be live.

“Mechanically operated musical instruments may be used only in an emergency and during intermission periods in regular programs.”

“Mechanically operated musical instruments” was a fancy way to refer to phonograph players (though it also covered player pianos). The following month, the Bureau rescinded that exception for emergencies — professional broadcasting had to be live, period. That made it very expensive and logistically complicated for any station to sustain.

Media historian Shawn VanCour calls this the “specific date at which the centrality of liveness to radio’s identity was consolidated.” (Making Radio: Early Radio and the Rise of Modern Sound Culture, 23). As he points out, even if audio recording technologies of the 1920s were not advanced, liveness was still a choice that regulators decided to impose.

The Bureau of Navigation’s Radio Service Bulletin, Sept. 1922.

Were records…sinful?

The Commissioner of Navigation, David B. Carson, was a retired railroad regulator from Tennessee hired for his knowledge of river boats. The justification he left behind about this decision to ban recorded material is a bit obtuse. In February of 1922 he wrote to his boss, Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover:

The action was taken for the purpose of preventing interference and to stop broadcasting by amateurs of phonograph records, which are not enjoyed by the public but at times becomes annoying.

It’s true, scratchy phonograph records sent over staticky signals probably sounded bad. Still: “But at times becomes annoying”? What is that supposed to mean? I haven’t seen evidence that the Bureau cared about the rights of music publishers, who were upset about recordings being broadcast. (ASCAP managed to win a suit to collect blanket licensing fees from radio stations in 1923).

Carson’s original memo is buried somewhere in the National Archives in Maryland, and I would love to scan it for more clues some day — but for now I (and all the sources I’ve read) have to rely on one article that cites the original: Marvin R. Bensman’s 1975 “Regulation of Radio by the Department of Commerce, 1921-1927” in American Broadcasting: A Source Book on the History of Radio and Television. (Thanks for indulging my nerdery, and let’s hear it for all who toil in the archives.)

The great scholar of radio, Michele Hilmes, offers an educated guess as to the Bureau of Navigation’s motives in banning records on those classy Class B stations:

Given that in fact the public avidly enjoyed phonograph records, as witnessed by the very healthy phonograph and recording industry, this description [i.e., “annoying” —JB] must be attributed either to distinctions made about the nature of the public (those who were annoyed constituting a different and superior class to those who played and enjoyed recordings) and/or to the nature of the content of these records (some contents being more equal than others). Evidence exists to show that it was the suspicious nature of “jazz” that contributed to this definition.

So the ban on recorded material may have started, at least in part, as an attempt to suppress jazz, which really did freak out many white people at the time. (Aside: I have a cameo performing the words of anti-jazz, or as she would prefer to say, anti-SIN crusader Anne Shaw Faulkner in this episode of novelist Hari Kunzru’s podcast).

Whatever the original reason, regulators soon let the ban on records fall by the wayside. They had bigger problems: the public had gone insane for radio, and too many people were demanding broadcast licenses. (“Everyone wants a radio station” is the “everyone wants a podcast” of 1924). The bureau had to force stations to share broadcasting frequencies by limiting them to a few hours per day in crowded markets. One of those license holders, Zenith Radio in Chicago, went on the offensive and decided to blast through time reserved for a Canadian station (sorry, Canada). The government tried to shut Zenith down, but a judge ruled that the Department of Commerce actually had no authority to regulate radio at all — so for a year, absolute chaos ruled the airwaves.

That year was 1926 — also the year Radio Corporation of America started the first commercial radio network, NBC. The following year, CBS established its network. Both built their business models around live programming that emanated from central studios in New York to affiliate stations via dedicated telephone lines. This was the clear, professional-sounding radio that people hoped would cut through the chaos and justify all the expensive sets people were buying.

Radio Broadcast, the WIRED magazine of 1926.

How did recordings threaten the broadcasting business model?

The new commercial radio networks paid AT&T huge sums for their lines. Without live programming, it was hard to justify that expense. But starting in the 1930s, a new sound-recording technology called electrical transcription started to encroach on the network business model. Transcription was a fancy way to quickly cut single records that sounded much clearer than average phonograph records of the time. Some individual stations and producers began recording their radio productions to transcription disks for direct distribution to stations, a practice the networks discouraged but couldn’t stop.

Alexander Russo writes about the tensions of this era in his fantastic book Points on the Dial. He features a quote from NBC President Merlin Aylesworth, who in 1930 planted the network’s flag again on liveness:

“If radio is to become a self-winding phonograph, it would be better to disregard radio entirely and go back to phonographs and records, than to waste the all too few wave lengths available for living speakers.”

Russo describes how network execs argued that live radio made for better listening — while also convincing regulators that pre-recorded programming was deceptive. In 1927, Congress created a new Federal Radio Commission to bring order to the airwaves. One of the first things it did was to issue a ruling requiring stations to announce transcription recordings both before and after playing them, like a little content warning. The ruling remained in force until late 1931, but even after that, NBC and CBS kept their ban on the use of recorded sound in their productions, except for recorded sound effects.

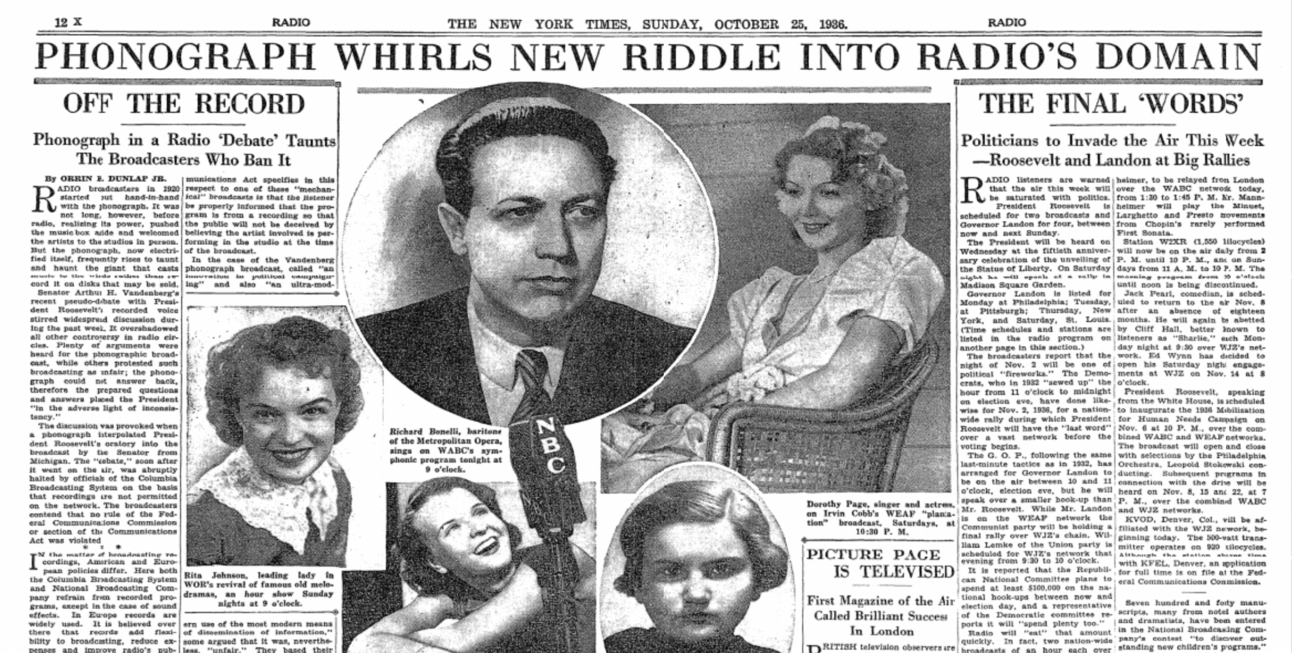

Radio: NYT is ON IT.

Why this obsession with banning recorded sound, even as its quality kept getting better?

“Because radio networks had nothing to sell beyond the sounds they transmitted, the processes involved in making those sounds were at the center of their business strategy,” writes David Morton in Off the Record: The Technology and Culture of Sound Recording in America. “Through the late 1940s, the networks were able to contain the threat posed by record-using upstarts, and in the process created the lasting impression that recorded sound represented a second-rate form of entertainment.”

In his epic 1977 dissertation on the use of recorded sound on American air, Michael Biel points out that internally, NBC started to doubt its liveness policy. Engineers who visited the BBC saw how that network experimented with recording technology, such as the crazy-looking Blattnerphone. NBC had the capability record its programming, too. Biel quotes a memo by NBC VP John Royal in 1936, who wrote: “We would save a lot of money in wire costs if we could use records. But the effect on the agencies might be more disastrous than the improvement we would make.”

The “agencies” were the ad agencies that were starting to produce most of the prime-time programs over network air, paid for by their clients. Many agencies would happily leave the expensive network fees behind if they could deliver their programs on disk to stations directly. So to ward off this threat, NBC and CBS believed they had to double down on the ban.

During World War II, the networks’ live-fetish placed exhausting and dangerous demands on correspondents in Europe:

CBS and NBC preferred to report live via shortwave links, even if that meant coordinating events internationally, tying up expensive transoceanic radio channels, and stringing hundreds of yards of microphone at the scene. Some network reporters, including Edward R. Murrow, broadcast from the relative comfort of the London rooftops; others, like H.V. Kaltenborn, found themselves dodging bullets as they attempted to drag long cables into the battlefields.

— David Morton, Off the Record, 61

Even Edward Murrow came up against the recording ban when reporting for CBS from London during the Blitz in 1941. He once used a recording he’d made of a barrel organist performing on a devastated street. “New York reported great response to records last night…but said I must have misunderstood as there was no relaxation of the ban on recordings other than sound effects, and I should not have used music or talk,” he wrote his wife. (See Alexander Kendrick’s biography of Murrow, Prime Time, 221.)

Meanwhile, as Michael Biel notes, Canadian and British war correspondents could record eyewitness reports using portable recording devices, and then go to a safer location to file. The Armed Forces Radio Service also used new, battery-powered magnetic wire recorders to great effect, and much of their reporting wound up on US air. (Biel, 1031; Morton, 61-62)

Still, at least in theory, NBC and CBS clung to their recording ban after the war, though with more major exceptions, as I talk about here. Variety, in its snarky glee, called the ban as “Anti-Wax” — a reference to old-timey wax cylinders. And they wondered what it would take to melt the anti-waxers down.

Variety headline, Nov. 13, 1946.

What did bring the recording ban to an end?

It wasn’t news reporters or documentarians, or even advertisers, who finally ended the all-live conceit of the networks. It was superstar crooner Bing Crosby, who had grown to hate the pressures of live broadcasting. You can hear more about that saga over at Radiolab.

The ban finally ended in 1949. But by then, the network bosses were placing all their bets on television anyway, and importing Hollywood film technology. Television was more expensive to produce than radio, and it started to feel ridiculous to air a show only once. Soon, the re-run was born.

But the belief that authentic broadcasting is live broadcasting has stayed with us. Every time we see a reporter risk death to report on a hurricane; every time we gather to watch (and bet on) a sporting event; every time we judge a debate performance or wait for an actor to flub their lines on Saturday night or sue a news program for editing, some ancient radio ghost is pleased we still believe in live first, and wax last.