Are we making something for that’s going to last even a minute longer than we do? What is the meaning of our work in the long term? If you’re in a creative profession, you may ask such questions — and if you’re an audio producer, you probably aren’t getting satisfying answers. But there is hope: scholarship!*

Scholars can help audio producers gain insights into bigger patterns at play and the historical context of what we do. That’s why I love the work of Northwestern associate professor of communication Neil Verma. His 2012 book Theater of the Mind helped me understand radio’s “Golden Age” — how writers, producers and engineers back in the 1930s and 40s invented new forms in the face of churning technological and commercial change. Verma’s newest work, Narrative Podcasting in an Age of Obsession, takes his century-long view of audio and turns it on the forms we are building now. He starts off with the question, “Why are podcast hosts often obsessed (or obsessed with someone else who is obsessed), and how well do these obsessions transfer to listeners?”

Podcast Movement happened to be in Verma’s hometown Chicago this spring, so I pitched the conference a nerdy panel conversation. To my surprise, they said yes! Below, you see us in the Black-Mirror set-up of the main hall at McCormick Place, where three sessions ran concurrently with the audience and speakers wearing color-coded Bluetooth headphones.

What follows is an edited transcript of our conversation. We get into, among other things:

Vicarious obsession as an accidental podcast structure;

How to help Martin Scorsese recreate an historically-accurate radio drama;

Why it’s been so hard for scholars to study audio;

How historical ignorance is both a blessing and a curse.

I hope you’ll enjoy our conversation as much as I did. At the end of this post, you can find a special discount code for readers of Continuous Wave to get 30% off Verma’s new book.

On stage at Podcast Movement, April 2025 (credit: Mike Bergonzi)

JB: Why study podcasting in the first place?

NV: So I think of myself as a radio historian. That's the field that I got most interested in in graduate school. I wrote most of my books about it. Most of my professional contacts are radio historians. And for a long time, radio history was kind of a sleepy backwater of Media Studies.

Then about 10 or 15 years ago, when podcasting started happening, it sort of happened around me, rather than me seeking it as an object of study. And being here in Chicago, I also had a lot of professional contacts with people at the Third Coast International Audio Festival, these great producers of narrative work. I got more and more interested in podcasting and how it related to some of these themes, questions, techniques from history.

Gradually over time, I developed a practice of listening to large bodies of material, of podcast episodes and shows. I tried to figure out, what are some of the deep structures, some of the deep techniques that kind of recur throughout and across the form?

JB: I'm a podcast maker — but I'm also an editor, and so I'm curious about how our form works. Reading somebody like you, who's on the outside, but is really deeply listening to our work and listening for patterns? It’s a real eye opener.

You start off talking about why so many podcasts center around obsession, especially Serial, but also Missing Richard Simmons or Wind of Change. Everybody's obsessed all the time, and you talk about this as a trope, but also as a storytelling technique that we all reached for at around the same time.

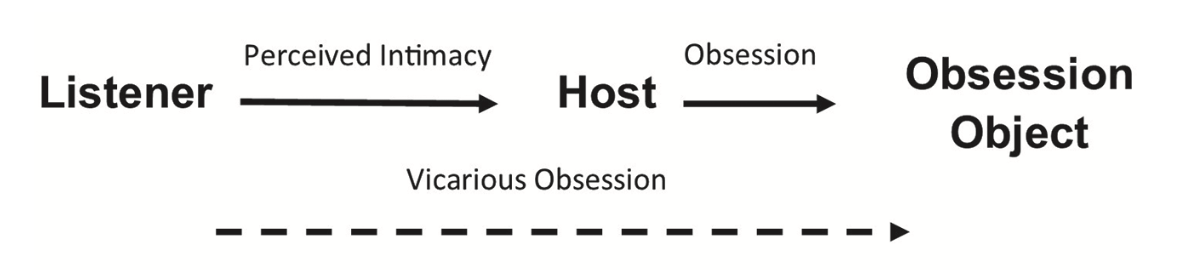

(Diagram from Narrative Podcasting in an Age of Obsession, 55)

NV: I think anyone who's at this conference has probably had this experience, where they fall into a podcast or a topic or a story or a case that they actually have no personal involvement in, or even interest in. Why is it that we get compelled or drawn into a subject matter that ordinarily, in our normal lives, we wouldn't care about at all?

It turns out that one of the things that you see in a lot of podcasts, especially from Serial until about today, is that a lot of podcasters start out their project — or start out their season, or start out their episode — by either confessing to, or introducing us to, a person who is obsessed with some specific object. You might not really care about it, but by virtue of the fact that you have a kind of intimate connection to the host of the show, their obsession transfers into you in this really interesting way.

So I came up with this notion of vicarious obsession — that it might not be something that you yourself care about, but because it's mediated through this other entity, you feel connected.

JB: One of the really interesting things about this book is you [gestures to assembled audience of podcasters] might find your own work in the index. You’ll find your friends in the index. I'm in the index. Neil, you have this 100-year-long view of our work because of your deep understanding of radio. Sometimes you're calling us out, like: “Why don't you know that you didn't invent all this? You are re-inventing it, but also in total ignorance of the fact that it's already been invented!”

NV: I am of two minds on this. I think it's natural to think, “Well, why don't you know the history of your own field?” But on the other hand, it's kind of glorious to not know the history of your field, right? There are many other kinds of art forms that feel very weighed down by a need to pay homage to the great civilizations of the past, and often those are very patriarchal traditions. Often they're kind of fussy and old.

Throughout radio's history, there were lots of people who were ignorant of those who came before them. There are radio writers from 1938 who had never heard anything from the 20s. There are radio writers from the 1970s who'd never heard anything from the 30s. Part of radio's strength is the fact that it is reinventing itself at different moments, in different media, for different communities. But that's also part of its weakness.

JB: You were a consultant on the last scene in Killers of the Flower Moon (Apple TV, 2023). It ends with a radio play, and director Martin Scorsese wanted it to be a really accurate depiction of how radio plays were done live. Can you talk about how they found you and what you did?

NV: So I'll let you in on a secret, which is that every “egghead professor” like me wishes that someday someone is gonna, like, tap you on the shoulder and ask you for your expertise on something. And this is kind of what happened!

It was during the pandemic, and I'd actually read the book [David Grann’s Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI]. It's a horrific story about murders of the Osage people by a group of exploitative white people in Oklahoma in the 1920s.

When they [Sikelia Productions] came to me, they said they wanted to end the movie with a radio play. It turns out there's actually an archival radio play from the early 1930s that was based on this story. But it takes all of the Native people out of the story and just makes it about the “heroic” FBI people, which was the convention of crime dramas of that period.

So they came to me and said, “How do we make this? What sound effects would we use? What microphones would we use? How would we set it up on the stage? Let's imagine this in a credible way.”

Martin Scorsese’s idea was to use this as a way of showing how history is re-narrated, and people are written out of it. Certainly human suffering is written out of it.

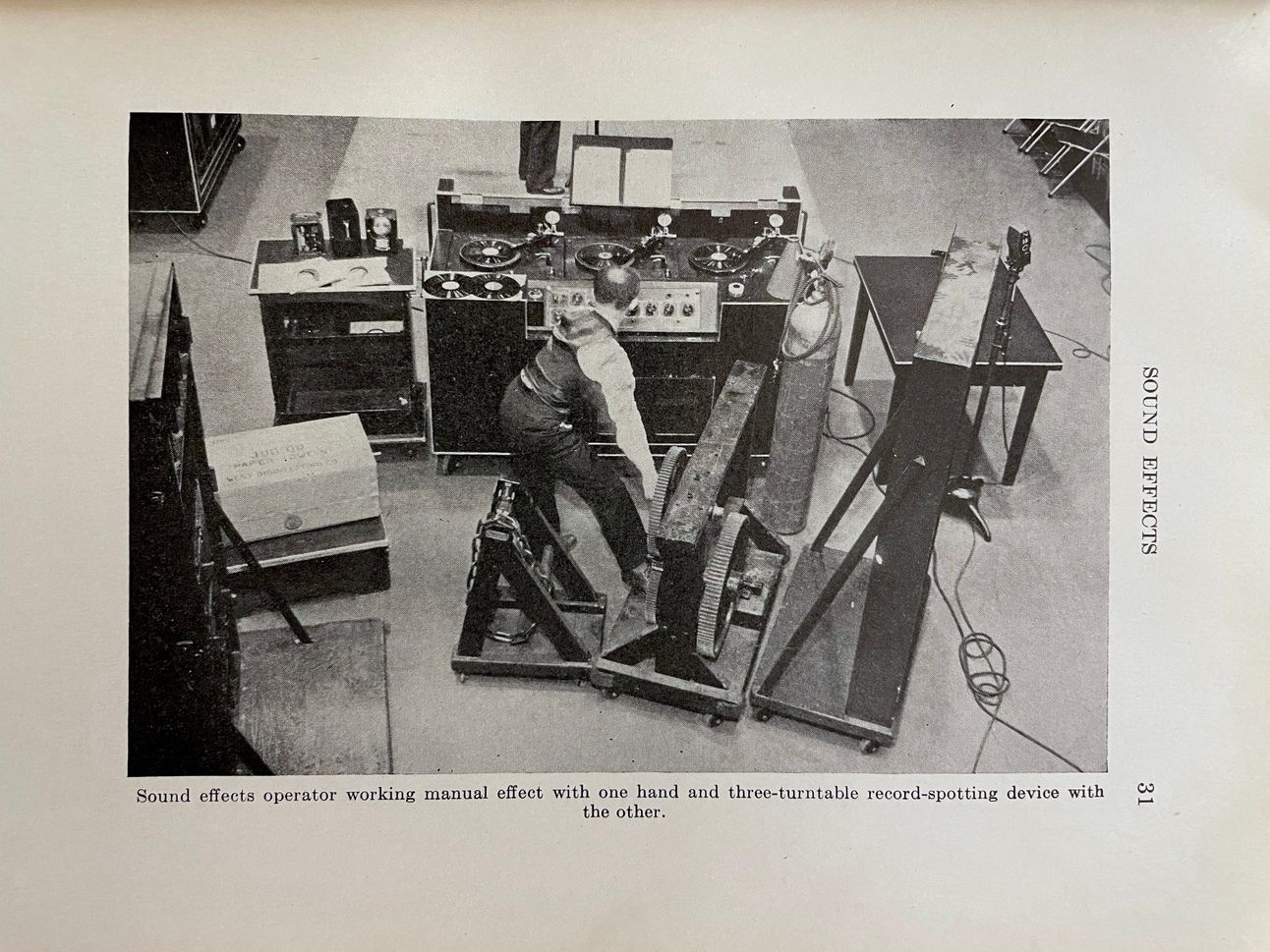

Most people, when they make or think about old radio plays, they have this very corny idea of it. Like, people using coconuts for [the sound of] horses and things like that. The way that we made this was very straightforward way: Imagine these are real people who really make radio plays for a living. This is just a normal part of their lives. How do we imagine the scene as they would have imagined it and improvised it?

We ended up devising period-appropriate sound effects. I have a large archive of different radio manuals [that show] how some of these kinds of scenes were written, devised, orchestrated. We also looked at a lot of archival photos of how studios and stages like this were actually set up in this period. All of that was to empower the art directors and give the set people a sense of, the actual texture of this work. It was a huge process. Actually it took months to put together, and I'm really proud of it.

It’s also a kind of indictment of this era of radio. In the early 1930s, “true crime” radio was huge. Many of [the shows] were quite violent, but also a lot of them were really there to just celebrate the FBI, and talk about how great the FBI is.

JB: You worked with somebody who is an expert in making sound effects. They didn't call it “foley” in radio.

NV: No. So foley is is the term that's used in filmmaking for spot effects, like using a chamois towel to make it sound like someone's choking to death, or something like that. In radio, it's a convention that comes actually out of vaudeville. Vaudeville theater often had what were called “trap drummers,” sound-effect artists who were able to make exaggerated effects when things were collapsing, when trains were coming, when bells were ringing — those kinds of things. And that convention slipped into silent film. Silent films were not typically silent. They often had people performing music or performing sound effects along with them.

My friend Nick White, who lives nearby, has amassed a world-class collection of the actual devices that were used to make these sounds in 1920s cinema. Really interesting guy. That tradition, the film tradition of foley effects, and the radio tradition of foley effects — it kind of cross-fertilized in this period. Nick was a perfect person to help bring about the scene, and I loved working with him and the crew to design some of the sound sequences.

JB: We're here at a podcast industry conference. What are some of the patterns that you see us repeating that people in the past have already been through? I mean, television comes to mind, but I don't want to ask a leading question…

NV: The main takeaway I want to give you is that the history of radio is the history of constant reinvention. It's a medium that was never constant. It was originally a replacement for telegraphy, right? Originally, the medium was called “wireless,” because you could send a message from one place to another place without using a wire, unlike using a telegraph. And then it was reinvented for military purposes. It was reinvented as broadcasting. In the 1940s, the coming of FM was an enormous change in in how the industry worked.

A lot of countries didn't have commercial radio of any kind. In the United States, that's the way we went. Most histories of media you've probably read say the radio age ends, and the television age begins, in the 1950s. But it's not exactly true. In the 50s, radio becomes a jukebox for rock music, and it completely changes its role in society. The [radio] industry has grown and collapsed many, many times.

JB: It's like The Matrix!

NV: Yeah, it's like that part of The Matrix where you find out that this fictional thing has happened several times. I think that often these industries change, and they change quite suddenly, and they change in ways you don't expect.

JB: You've talked to me about how hard it's been for scholars, not only to get respect from their colleagues in cinema studies — but also how audio scholars had a problem just accessing the archives until recently. Can you talk about that a bit?

NV: Studying audio is a funny thing, because for a long time it was impossible. Imagine the 1930s, 40s, 50s in the United States. You have hundreds of radio stations, three or four big networks, constantly broadcasting material. For years and years and years. Not all of it was recorded, but a lot of it was. But no one had any incentive for providing those recordings to anybody. A few of them would be made into records, and later CDs, and commercially packaged and sold. But that was really for a kind of niche audience. So it [all] moves to the periphery of culture and sort of vanishes for a really long time.

What happens in the early 2000s is the advent of the .mp3 transforms our experience of this archive. Twenty-five years ago, if you wanted to study radio, you would have to go to the Library of Congress and sit in their listening room and take one thing out after another. It's taken enormous amount of time, but now you can download the same material in .mp3 format, and there's far more than you could listen to in a lifetime. So we're talking hundreds and hundreds of thousands of .mp3s, and there's no finding aid for you. There's nothing to make it easier.

JB: It's just a big pile.

NV: It's just a big pile of stuff, and we've gone from too little to study to too much —that's made it a bit of a challenge. But the good news is it's better to have a super abundance than to have nothing.

JB: There's also this new field, Sound Studies.

NV: Everyone's like, “Wait a minute, this is a major form of communication that millions of people experience. Why aren’t we studying it?” So there's this whole new field, and it encompasses more than just radio and podcasting. It's all the ways that humans express themselves through sound: sound studies. It's mind-blowing to see how much people are learning afresh about our own history through sound.

I think one thing that's important for people at this conference is really to take sound seriously. To think about it as a plastic dimension of your work. When you create a podcast, when you talk to other people, it's not just the words that they're hearing. They're hearing voices. They're hearing the sounds of the place that you're in. They're hearing the way [those elements] illustrate it, the way you musically underscore it. And that is a different kind of encounter than mere language.

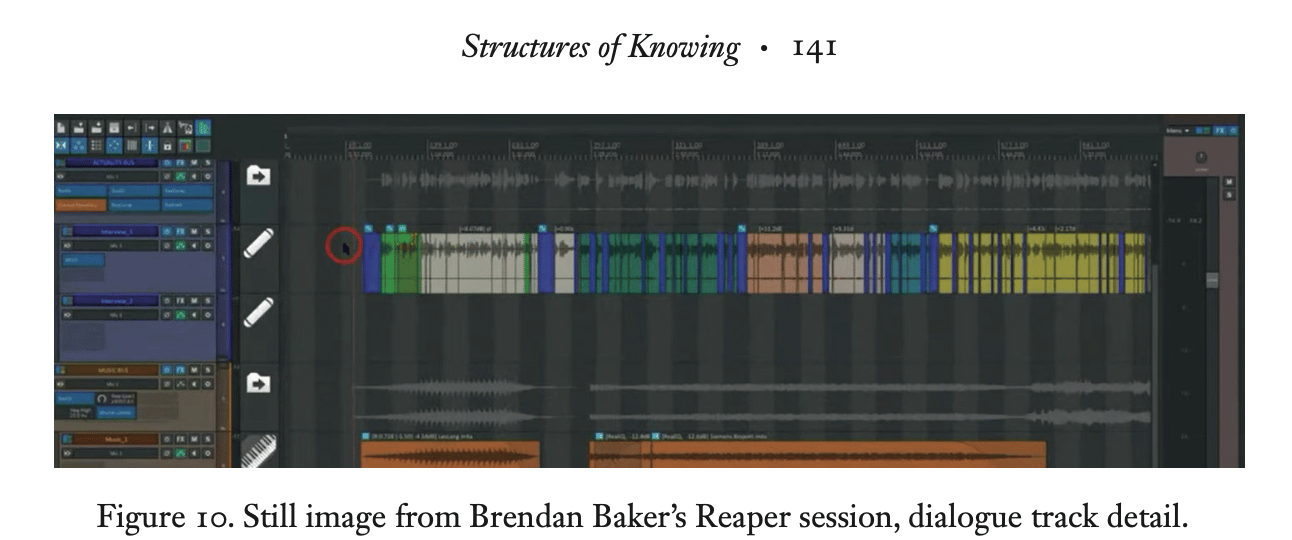

(illustration from Narrative Podcasting in an Age of Obsession)

JB: You say in your book that scholars should not only be listening to our work, but also studying, if possible, our actual editing sessions.

NV: Yeah, imagine it this way. One day we're all going to be gone, but hopefully some of the work that you made will endure, right? But what people won't be able to see is how you made it. There'll be no archive of your DAW session that shows how you mixed different things, and where you brought different resources. That’s the equivalent of those production photos we used when working on Killers of the Flower Moon, or the old scripts that you can find at university libraries: The backstory of how things were made. In a perfect world, I'd love to be able to preserve that [for podcasts] too — not just the final product, not just the sound, but to see people's work processes. It's challenging, because you have to be literate in those kinds of programs as well.

[Here we got a question from the audience about the popularity of “video podcasts.”]

NV: I don't know a lot about video. I can't tell you how to make a good video, but I can tell you it really changes the game.

There's a radio writer named Erik Barnouw, who was one of the first historians of radio and also a radio writer at CBS. He wrote this great book about the different affordances that come along with audio formats. And one of the things he talks about is “the shifting mind world,” which sounds very fancy. But what he means is that, in audio because you can't see something, it's very easy for you to create images in the listener's mind, [images] that are actually impossible or illogical. And for [Barnouw], that was a strength of audio.

We're so used to thinking about what audio doesn't have — but that's something that audio really does have, that you can't actually recreate in a video or visual format. When we give someone a face, we give someone the image that we were previously conjuring, right? So I feel like that's something to be mindful of, that in the shift to video, a lot of the affordances, the things that make audio great, are going to stop.

Thanks for reading our conversation. You can order Neil Verma’s Narrative Podcasting in an Age of Obsession here at the University of Michigan Press. Enter the code UMS24 for 30% off — and you’ll be supporting a non-profit academic publisher.

*While you’re stocking your shelves, there’s a raft of other new books in the realm of podcast studies: Siobhan McHugh’s The Power of Podcasting (2022); David Dowley’s Podcast Journalism (2024); Podcasting: The Audio Media Revolution (2019) by Martin Spinelli and Lance Dann; and the gigantic Oxford Handbook of Radio and Podcasting (2024), edited by Michele Hilmes and Andrew J. Bottomley.

From Radio Directing by Earle McGill (1941), one of many great historical sources recommended by Neil Verma.

Business as usual? No thanks.

The problem with most business news? It’s too long, too boring, and way too complicated.

Morning Brew fixes all three. In five minutes or less, you’ll catch up on the business, finance, and tech stories that actually matter—written with clarity and just enough humor to keep things interesting.

It’s quick. It’s free. And it’s how over 4 million professionals start their day. Signing up takes less than 15 seconds—and if you’d rather stick with dense, jargon-packed business news, you can always unsubscribe.