In this Nerd Villain Era edition:

A woman came up with that™

How to go from starving artist to master of the universe in 100+ difficult steps

OG beef with the Associated Press

OG pizza hate

Hate

I have to force myself not to think about how email newsletters actually work: that the very moment I hit “send” on this, it will land in your in-box. Perhaps you will delete, ignore, or read it — that’s all fine. What frightens me is the instantaneity. I’m an editor, the person who’s supposed to anticipate and fix mistakes before they go out. I am uncomfortable with this business of reaching others at the speed of light.

The first day anyone felt this kind of instantaneity was May 24, 1844. That’s when Samuel Finley Breese Morse sent the inaugural telegraph message from Washington DC to Baltimore. It was a quote from the Old Testament Bible’s Book of Numbers: “What hath God wrought?”

What indeed. “Before the telegraph there existed no separation between transportation and communication. Information traveled only as fast as the messenger who carried it,” the media scholar Daniel J. Czitrom noted back in 1983, well before our current wrought-ening got truly out of hand with the Internet. (Update: I’m finally reading James Gleick’s The Information, which makes a good argument that “talking drums” amongst tonal-language speakers in Africa carried news as fast as any telegraph would.)

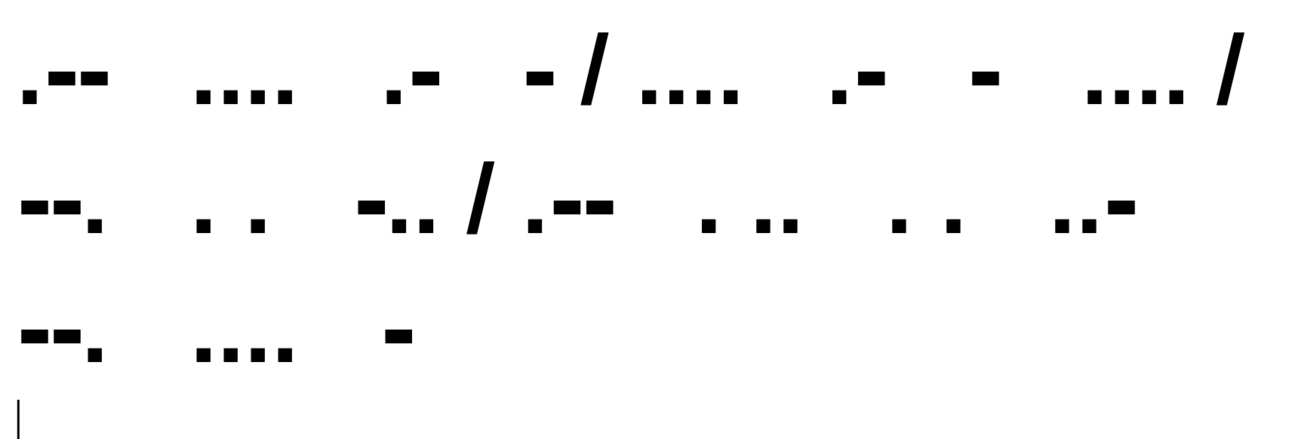

Every email that we now send — every podcast, broadcast, Zoom invitation, group chat, LinkedIn/X/Facebook/Bluesky post, every Pinterest board, streaming half-time show, and reply-all pile-up — to a one, they all go back Samuel FB Morse, the man who lay claim to having invented the telegraph, and who definitely invented the dot-and-dash alphabet code that soon enough allowed messages to fly around the world.

Samuel F.B. Morse was a real piece of work.

Morse’s story immediately bursts out of the mental containers we use to hold inventors. He was a talented painter, a patriot who dreamed of living in Europe, an ardent anti-Catholic who accepted medals and accolades from Catholic states. He expected great things out of life and mostly got them, but not the way he expected, and not without constant turmoil and really bad takes.

Subscribe to Continuous Wave to read the rest.

Become a paying subscriber of Continuous Waver to get access to this and dozens of deep dives plus exclusive content.

UpgradeA subscription gets you:

- Continuous Wave logo stickers

- Personalized letter explaining the origins of the CW logo!

- Access to paywalled articles through 2026.