The missing link

Note from Julia: I named this newsletter not in tribute to the engineering explainers that crop up in any search for the term “continuous wave” (though, of course, sound-science is based). No, the name exists because what we lack in audio production culture is continuity — and this history project tries to address that problem, post after nerdy post. When we don’t know what came before us, or why things turn out the way do, then the same patterns keep repeating themselves, always disguised as something new.

US audio culture fell into major discontinuity starting in the mid 1950s, when television either ate or discarded the network “Golden Age” live radio productions. Soon enough, radio was the realm of recorded music and a smattering of news — great for pure emotions and information, not so much for stories or characters. And poetic, risk-taking creativity? Forget it.

But in a cycle that is now becoming familiar to podcasters, spoken-word audio still kept finding an audience. As the big networks abandoned radio, counterculture acted as a reservoir, especially at nonprofit stations like Pacifica’s KPFK in Los Angeles. The station’s volunteers spawned new types of creative work in audio, especially Firesign Theatre, four guys who banded together and produced a spate of best-selling comedy albums in the late 1960s through the 1970s. Even if you haven’t heard a Firesign album, their influence has permeated far and wide, from Ren Faires to Hip-Hop samples to DIY religion.

I remember seeing Firesign albums around in my youth, perhaps while hearing one of their routines partially recited by a boyfriend or two. Firesign’s humor, often called surreal and sometimes compared to Monty Python’s Flying Circus, was full of sonic twists and barbs, plus multi-layered jokes and references that rewarded repeat listens. Of course, I had no idea how many of those references, and Firesign’s production techniques, were adapted from and influenced by vintage radio. It turns out that the troupe (Peter Bergman, Phil Proctor, Phil Austin and David Ossman) are one big missing link between narrative audio’s past and its present. This I learned from a fascinating new book by Jeremy Braddock, Firesign: The Electromagnetic History of Everything as Told on Nine Comedy Albums.

Braddock, who teaches in the department of Literatures in English at Cornell, has graciously agreed to share the following excerpt of his chapter on Firesign’s second album, which came out in 1969 and was, as you will read, the Firesign album perhaps most directly connected to radio’s past. The first side is a series of skits which start off (allegedly) in a moving car sold by one Ralph Spoilsport of Ralph Spoilsport Motors. (If you want to listen to the audio Braddock describes below, click here. And you can find links to all of Firesign’s radio influences and sources over at Jeremy’s newsletter).

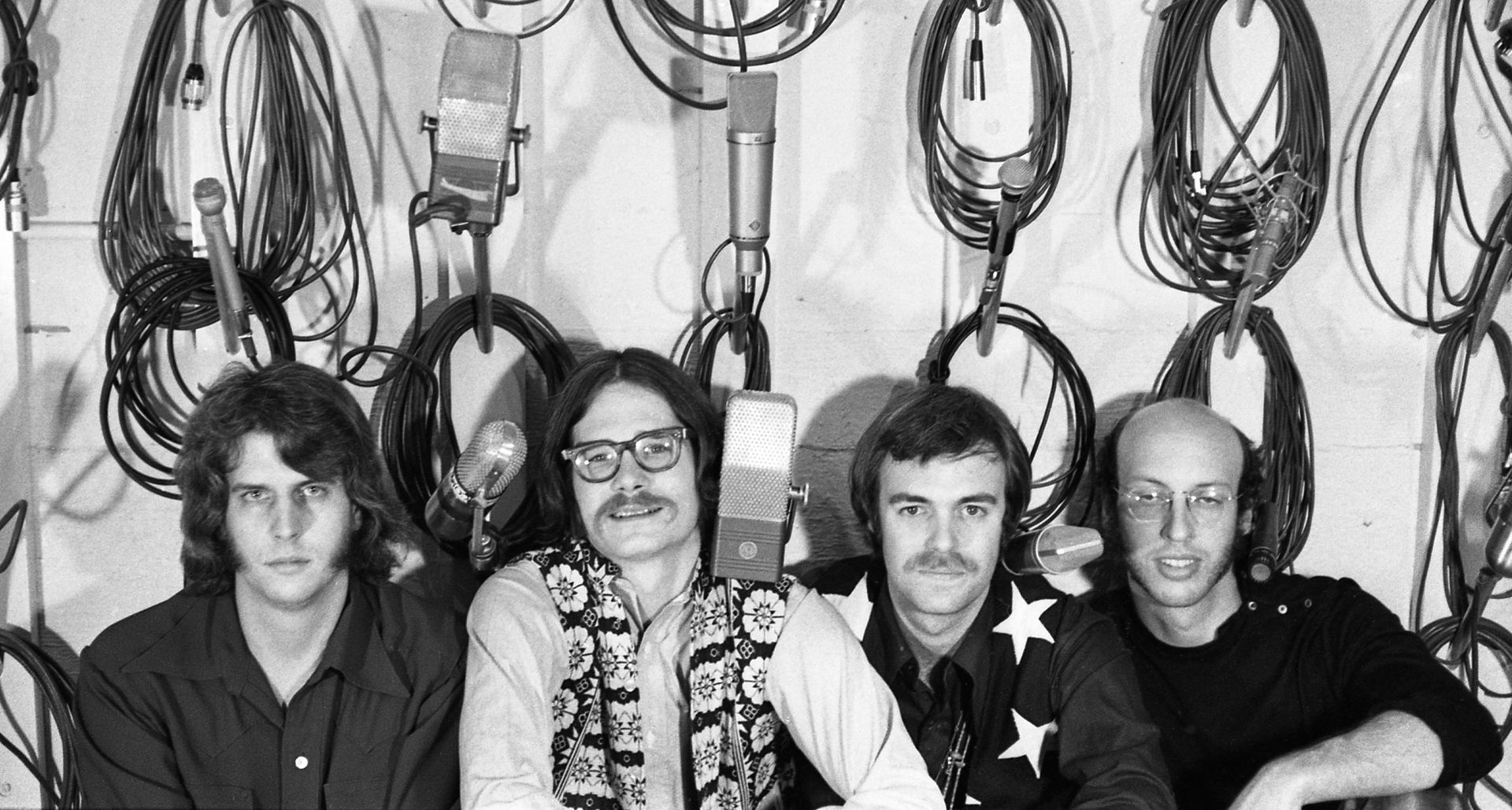

Philip Proctor, Phil Austin, David Ossman, and Peter Bergman at CBS Columbia Square Studio, July 1969. Photo by Frank Lafitte. Courtesy of Sony Music Archives.

And now, here’s Jeremy Braddock:

Contradictory Space

After the slam of a car door, the acoustics immediately become warm and nonreverberant. We are with the protagonist as he drives off, hearing him talking to himself, he discovers that the car’s climate control is able to conjure different total environments while paradoxically remaining, for now, a car. There’s winter wonderland, spring fever, and the eventually chosen “tropical paradise,” which will be (cue thunderstorm) the album’s first reference to Vietnam. After about nine minutes, the car will have disappeared entirely but not before it is the site of another astonishing contradictory soundscape. A series of road signs, dramatized verbally, approach and recede from the listener via volume swells and move across the sound field from center to right. It produces an uncanny effect of movement on the highway, even as one subset of these “signs” contradicts this sense of movement by staging a version of Zeno’s paradox (Antelope Freeway one-half mile, one-quarter mile, one-eighth mile, one-sixteenth mile…one two-hundred and fifty-sixth mile…), a contradiction of space and time together.

Starting with the first side of 1969’s How Can You Be in Two Places at Once When You’re Not Anywhere At All, the hallmark of every Firesign Theatre album was the way each surreal, densely plotted narrative was realized in meticulous sonic depth and detail. Both were self-evident products of what Brian Eno would later call “in-studio composition.” With a contract that traded mechanical royalties for unlimited time in the studio, Firesign was able to write and record iteratively and deliberately. In a way that resembled Geoff Emerick’s work with the Beatles, their new Columbia engineer, Bill Driml, was open to breaking with established protocols, collaborating with the artists, and experimenting with new sounds. And, as they well knew, they were also availed of the state-of-the-art affordances of the CBS Columbia Square studio, newly installed with eight-track recording equipment.

Located at the corner of Sunset and Gower in Hollywood, Columbia Square was where The Byrds had recorded “Eight Miles High,” “2-4-2 Fox Trot (The Lear Jet Song),” and “C.T.A.—102,” and it was where Moby Grape had recorded their first album and where Brian Wilson had recorded vocals for the Beach Boys’ “Good Vibrations” and Pet Sounds. These were all recordings that had experimented with quasi-narrative “architectural” effects. Namechecking “Yellow Submarine,” David Crosby said, “If we can put anybody on a trip where they feel the same things that we felt going up in that airplane then we’ve succeeded.”

But in a way that was not true for the musicians, the new Firesign album also directly invoked the longer history of Columbia Square.

Columbia Square showing the CBS Studios in Hollywood, 1938. University of Southern California Libraries and California Historical Society. (Public domain)

What would it have sounded like?

Built in 1938, the International Style building had been overhauled by CBS in 1961, anticipating what an in-house journal called “the advent of stereophonic sound and its completely new process of recording.” It now complemented, and in some ways surpassed, the label’s legendary 30th Street studio in New York. The opulent Columbia Square had not been originally designed for recording but was rather a state-of-the-art facility made for radio broadcasting. As Neil Verma has pointed out, radio studios were at that time typically far more acoustically complex than those built for recording music. For more than two decades, Columbia Square was home to fabled programs from Jack Benny, Burns and Allen, and The Orson Welles Show to Suspense, Gunsmoke, and The Adventures of Philip Marlowe. The great playwright Norman Corwin regarded Columbia Square as radio’s “Mecca…There was not anything quite corresponding to its splendor in New York.”

With free rein to explore the premises, the Firesign Theatre discovered abandoned technologies and devices from the radio days throughout the building: there was the enormous echo chamber (which had since been used on musical recordings), a plethora of sound-effect devices for live Foley (doors, guns, wind machine, a board for footsteps), and the Hammond B3 organ made famous by Suspense. The most important discovery was a set of forsaken RCA ribbon microphones that were ideal for on- and off-mic voicework. These gave How Can You Be a spatial depth that [Firesign’s first album] Waiting for the Electrician did not have and were used on all the group’s subsequent Columbia albums.

So while the mesmerizing Zeno’s paradox/talking-road-sign sequence of How Can You Be required several up-to-the-minute technologies, not least the stereo movement abetted by the new eight-track tape machines, it also hearkened directly back to the eerie sound world of Lucille Fletcher’s radio play “The Hitch-Hiker,” which first broadcast from Columbia Square as an episode of The Orson Welles Show in November 1941. “The Hitch-Hiker” tells the story of Ronald Adams (Welles), a man driving across the country from Brooklyn to California. Setting out from his mother’s house in Brooklyn, he passes a hitchhiker on the Brooklyn Bridge, sees him again on the Pulaski Skyway, and then continuously as he proceeds across the country — events Adams conveys, with increasing anxiety, entirely from the driver’s seat of the car. The story becomes so deeply enmeshed with Adams’s psychology that the effect of the play is, as Verma observes, to confuse the space of the outside world with a state of mind; the “acoustic cocoon” is transformed into a place of paranoid projection. A final plot twist reveals that most of the story’s events have occurred “outside of natural time.” In a way, these are all things that happen to How Can You Be’s protagonist, too.

Firesign’s Phil Proctor would later explain:

“We wanted to produce the records as if radio had continued into the modern era with the full force of energy it had during its so-called golden age. What would it have sounded like?”

This is a succinct characterization of what would today be called media archaeology, a field of inquiry producing technical genealogies and countergenealogies, as well as what the scholar Thomas Elsaesser dubbed a “poetics of obsolescence.” Above all, its diverse strains are guided by “a strong sense/consensus that one should be ‘doing media archaeology’ rather than merely using it as a conceptual tool.”

Elsaesser also aligns media archaeology with the parallel development of “counterfactual history,” which could also be a dignified name for some of How Can You Be’s most notorious gags — spoiler alert: the president of the United States is named Schicklgruber — as well as a means of evoking another element of radio’s “golden age” patrimony, namely, its historical entanglement with disinformation and propaganda. In the 1938–39 Manual of German Radio, Schicklgruber himself (I mean Hitler) wrote that “we should not have conquered Germany without . . . the loudspeaker.” And by that time, Dorothy Thompson, the first American journalist to be expelled from Nazi Germany, had already remarked that “radio is to propaganda what the airplane is to international warfare.” Nor was radio propaganda an exclusively fascist concern. While the United States remained officially neutral, British international broadcasting worked to cultivate feelings of solidarity and sympathy between the two countries, something that had been another object of study at the Princeton Listening Center.

As the US entered the war, American commercial radio networks adapted their conventional genres and created specialized broadcasts to serve the war effort. The networks, in Gerd Horten’s words, “willingly disseminated government propaganda and successfully united much of the American public behind the war effort.” And although many, including Welles, had contributed, the undisputed laureate of American antifascist radio had been Norman Corwin. “We Hold These Truths,” his sesquicentennial celebration of the Bill of Rights, aired simultaneously on all four national networks in December 1941, eight days after Pearl Harbor. After many further programs, in May 1945, On a Note of Triumph celebrated the end of the war with another national broadcast; Columbia Masterworks released a six-disc recording before the end of the year. Both broadcasts had originated from Columbia Square in Los Angeles:

So they’ve given up.

They’re finally done in, and the rat is dead in an alley back of the Wilhelmstrasse.

Take a bow, G.I.,

Take a bow, little guy.

The superman of tomorrow lies at the feet of you common men of this afternoon.

This is It, kid, this is The Day, all the way from Newburyport to Vladivostok.

You had what it took and you gave it, and each of you has a hunk of rainbow round your helmet.

Seems like free men have done it again…

Far-flung ordinary men, unspectacular but free…

The Firesign Theatre knew the pieces well, both from the disc recordings and from print collections of the scripts (which helpfully included Corwin’s genial production notes), and they were drawn to his later experience as a writer blacklisted just three years after the war. One vector for Phil Proctor’s query — what would it have sounded like? — was therefore to wonder about the fate of Corwin’s gregarious antifascism and its “mystical vision of citizenship” in the Vietnam era.

Annoyed by his car’s “tropical paradise” sound world, the protagonist of How Can You Be selects the climate control’s “land of the pharaohs” as a means of escape. This choice elicits a pyramid, which may be in the Egyptian desert or on the back of a US dollar bill (or both). As the protagonist runs inside, the pyramid becomes “the only nice motel in town.” Ostensibly, we may all still be in the car, but the car is never mentioned again. Instead, the motel’s lobby becomes the site of an eight-minute Corwinian pageant in which the truisms of democratic citizenship are repurposed for the age of the imperialist war in Vietnam:

DC: And we took to them!

Eddie: And they took to us!

DC: And what do you think they took?

All: [chanting] Oil from Canada! Gold from Mexico!

Geese from their neighbor’s back yard! Boom, boom!

Corn from the Indians! Tobacco from the Indians!

Dakota from the Indians! New Jersey from the Indians!

New Hampshire from the Indians! New England from the Indians!

New Delhi from the Indians!

B: Indonesia for the Indonesians!

J: [cannon shot] Yes, and Veterans’ Day…

DC: But we couldn’t do it alone [Morse code sending under]

J: No! We needed the Hope, the Faith, the Prayers, the Fears

DC: The Sweat, the Pain, the Boils, the Tears

J: The Broken Bones!

DC: The Broken Homes!

J: The total degradation of . . .

B: Who?

E: You! [champagne cork pop and pour] The Little Guy!

The pageant, as can easily be seen, mimics Corwin’s rhetoric as well as his floridly extroverted style. The “Little Guy” is a signature Corwinism, a stagey update of the Popular Front’s “common man.” Updating it for late 1968, the Firesign Theatre revealed the way Corwin’s hortatory patriotism had been used to exploit the Little Guy while concealing the inegalitarian reality of the war (after first extending their first album’s critique of Native American dispossession). When at length the sequence concludes, the protagonist finds himself cheerily coerced into enlisting in the army (“Get in step with the voices of the feet already dead in the service of their country!”), after which he appears briefly to become African American and then disappears from the story entirely — a set of sonic figures signifying the true demographics of the Vietnam War. Black soldiers accounted for nearly one fourth of the fatalities in the early years of the war. David Ossman, who would later collaborate with Corwin on a fiftieth-anniversary broadcast of “We Hold These Truths,” began his working notes for How Can You Be with the unfinished statement: “The problem with Norman Corwin…” (The problem with the Firesign Theatre, meanwhile, was audible in their blackface answer to the problem of Corwin.)

With the protagonist now totally absent, the final seven minutes of the side involve a World War II vignette that concludes with a travesty of a USO-style singalong, which is titled, borrowing the SDS’s slogan from Chicago 1968, “We’re Bringing the War Back Home.” This performance is then revealed to have been the conclusion of a film broadcast on the Late Late Show for a Saturday Night, which is followed by a channel-surfing sequence of TV broadcasts that return us at length to Ralph Spoilsport, now selling weed rather than cars, who seamlessly segues into the final 150 words of Molly Bloom’s soliloquy from the end of James Joyce’s Ulysses as the sound of cars on the highway morph into an oceanic chorus of “yeses,” “Yes I will yes yes.”

The car has long since disappeared, the protagonist has gone, and the listener is left with the euphoric sounds of a gender-ambiguous speaker’s unconditional surrender. At the end of an actual broadcast day in 1969, listeners would have heard the national anthem.

Copyright 2024 by Jeremy Braddock.

JB: Thanks again to Jeremy Braddock for sharing a small portion of his mega-trove of audio history. Now be sure to go and get Firesign: The Electromagnetic History of Everything as Told on Nine Comedy Albums. Braddock also writes about more treasures and ephemera in his newsletter Giant Slide 19 Holes Underground Parking, including all the radio sources and influences cited above, here.