Plastic bubbles

Although I write mainly about audio, I am a creature of the High Age of TV network drama. I’ve already talked here about my affection for The Six Million Dollar Man (and his TV sister the Bionic Woman). But honestly, $6M guy was a minor figure in the pantheon of playground hits. First among our monkey-bar crew: The Boy in the Plastic Bubble, the heart-rending tale of an immune-compromised John Travolta, forced to live in an astronaut suit and kiss through a plastic barrier.

I learned about the wider world through TV sagas. Roots taught me about the slave trade and Black liberation. The Thorn Birds taught me about sexy priests. And The Day After, although I didn’t actually watch the nuclear-disaster drama when it came out in 1983, changed the direction of my life — all the fear-mongering induced me to study Russian in high school, to go on a tour of the USSR in 1985, and become a weird Cold War nerd forever.

Did I know as a child where all these high-prestige TV dramas came from? Of course I did! They came from Channel 8. Channel 8 was the best channel, the one you fought for control of the remote to watch. At some point, I learned it had another name, WFAA. I was only dimly aware of some other letters in the background: ABC, the American Broadcasting Company.

Broadcast networks are weird. They are the source, or at least a major facilitator, of the programming waters we swim in — even now in our fragmented era of streaming. But the household taps from which those waters emerge from are (also, even now) local station affiliates. In truth, we’re not supposed to think about the water plant, the pipes or the taps at all. We’re supposed to look past that plumbing and interact directly with the goods — remaining blissfully ignorant, pretend-kissing an imaginary John Travolta on the playground.

All of which is why, when the network ABC and its owner Disney Corporation temporarily body-blocked a longtime comedian host after threats from federal regulators, the audience did not like the sight at all, and laughed with relief when the system seemed to right itself.

This isn’t the first time that management of a TV network has gotten burned for misjudging its audience, especially when it comes to popular comedians. Plenty of people have written about that phenomenon (see the book “You Can’t Air That” for one history of comedy censorship on US TV, for instance).

We here at Continuous Wave are in search of deeper historical ironies. When it comes to ABC, those are not hard to find, because the network in fact owes its existence to a zealous federal regulator.

ABC: The Prequels

Sorry to yank you back to olden radio times, but as is the case with almost all stories about USA broadcasting, that’s where our saga begins. And like a famous Disney franchise, this story has prequels to the prequels.

As our guide, we have author Laurence Bergreen, who writes bestselling works of history and biography now. His first book, however, is out of print. Too bad, because the introduction alone is worth a read.

It is about a broadcasting system that has, over the years, shown itself capable of prophecy and betrayal, of years of mediocrity and moments of inspiration. It is about a business of overwhelming vanity and brutality, a business with absolutely no memory, but one whose every action is dictated by its own, forgotten past.

Sounds about right.

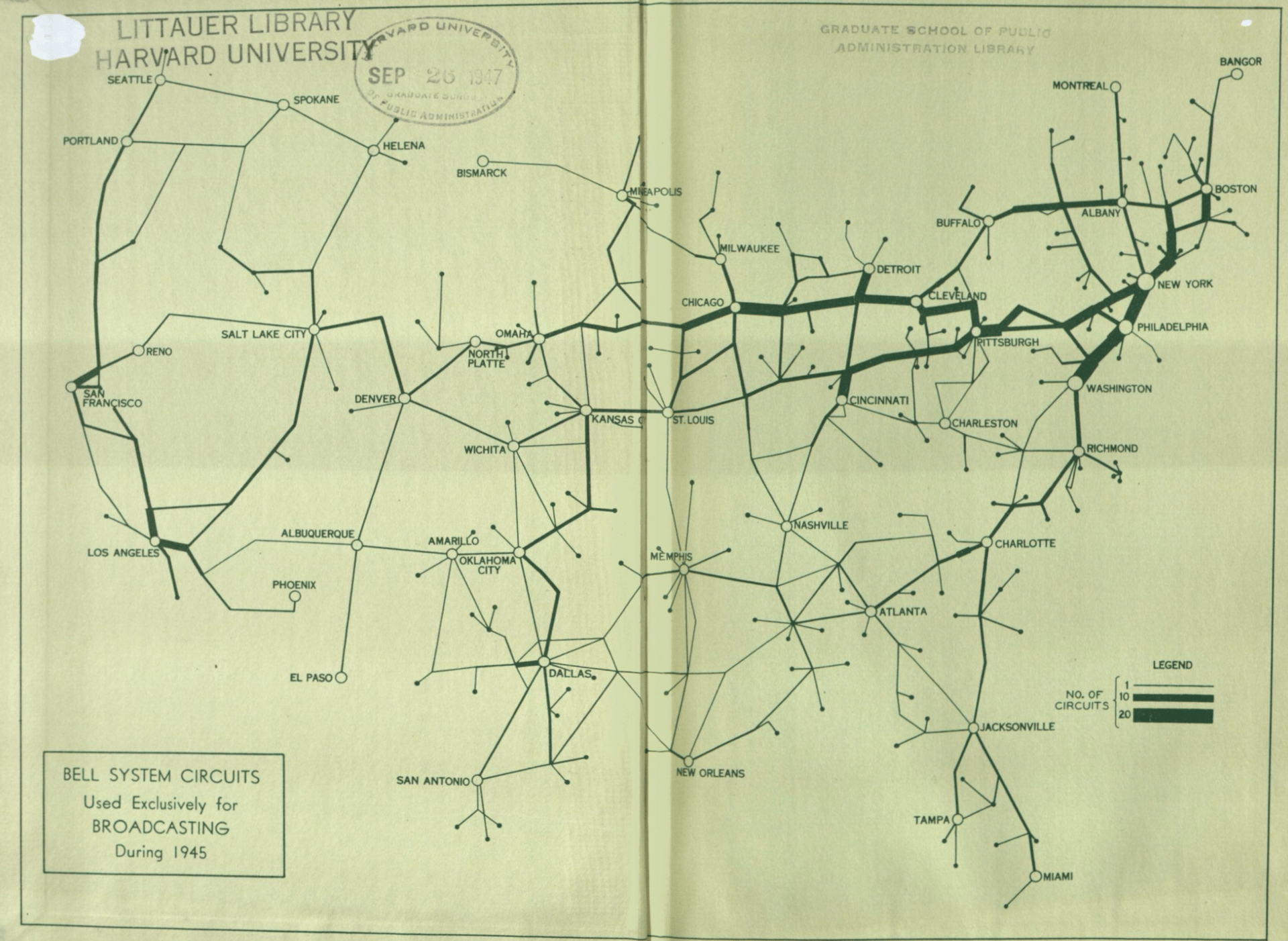

So in the beginning, there was only one broadcasting network in the US: the National Broadcasting Corporation, which started in 1926 and which I’m pretty sure will soon remind us of that centenary, “forgotten past” be damned. But it’s important to know that inside its early plumbing, NBC had two sets of pipes. The story of why, and what happened to those two sets of pipes, is going to turn into the story of ABC, I promise.

Several years before NBC came to exist, the telephone company AT&T invested big money to build an experimental radio station in New York, WEAF. AT&T figured that since they could charge for telephone calls, they also could charge “tolls” for blocks of time on their station. And they did that (you can hear a recreation of the first radio ad, an extremely dull real estate promotion, in this NPR feature).

The corporate telephone people figured out how to make money from broadcasting at a time when no one else knew how. But broadcasting quickly became a headache for them. Sometimes their flagship station sold airtime to journalists. And those news analysts said things that powerful people did not like. In one broadcast, HV Kaltenborn, then editor of the Brooklyn Eagle, criticized a recent decision by the US Secretary of State. See if that guy’s reaction sounds familiar.

The Secretary of State was tuned to the broadcast in the company of “a number of prominent guests.” He was embarrassed and angry. A Washington representative of the telephone company was called to the phone, and “Secretary of State Hughes laid down the law to him.” The word was relayed to New York that “this fellow Kaltenborn should not be allowed to criticize a cabinet member over the facilities of the New York Telephone Company” … They had originally embraced the “toll” conception with the beguiling thought that they could lease facilities without responsibility; this seemed a sound telephone approach. Now they were enmeshed in agonizing policy problems.

So the phone company was the first to feel the pain of relevant broadcasting. They decided to sell WEAF — and along with it, a proto-network of dedicated telephone wires they’d used to transmit programs to a few other radio stations. This whole experimental set-up went for a million bucks to a newish company, the Radio Corporation of America. RCA used this purchase to announce the formation of NBC.

But RCA already had its own, separate proto-network underway. It had been watching AT&T and worked to link its New York flagship station WJZ to other stations. According to lore, engineers at AT&T’s Long Lines division mapped the dedicated WEAF lines on their charts with a red pencil, and RCA’s with a blue pencil. In 1926, the two embryonic networks were combined into NBC. Still, RCA decided to keep the Red and the Blue separate. Some of the stations were in the same listening areas, after all. Now the Blue Network could become the place for “public interest” shows that didn’t make as much money but helped NBC’s image with the public and with regulators: children’s programming, symphony music, religion and public affairs. While the Red Network pursued the money-making course first charted by AT&T, the Blue Network could make up for its sins.

As anyone with a radio could attest, NBC used its Blue network as a “buffer” for the Red, allocating its high-rated, high-priced entertainment to the Red while loading the Blue’s schedule with public-service programs, where they would do the least damage to company profits. …NBC was in the enviable position of being able to counterprogram against itself to achieve an overall competitive advantage against non-NBC networks.

Fly bludgeons mackerel

After a decade of this, the good times at NBC were about to come to an end, thanks to an activist chair of the FCC named James L. Fly. Then as now, the Federal Communications Commission did not “license” networks, but it did control the licensing of affiliate stations. In the mid 1930s, the FCC got a complaint from the struggling Mutual Broadcasting System, furious about the difficulty of expanding its network in markets where the NBC Red-Blue hydra dominated.

Fly, a Texan who’d attended Harvard Law and run the Tennessee Valley Authority for a while, investigated and concluded that NBC was behaving in an anti-competitive manner. He couldn’t do anything about it directly, but he did put the heavy on affiliate stations in Red+Blue markets, saying they could lose their licenses. In the end, after losing before the Supreme Court, NBC had no choice but to divest. (I highly recommend Christopher Sterling’s chapter about this era in a collection of scholarly essays on NBC. Sterling notes that NBC was thinking about offloading the unprofitable Blue Network anyway).

Just to make his demand a little folksier, Fly told a conference of media folks that radio management reminded him of “a dead mackerel in the moonlight which both shines and stinks.”

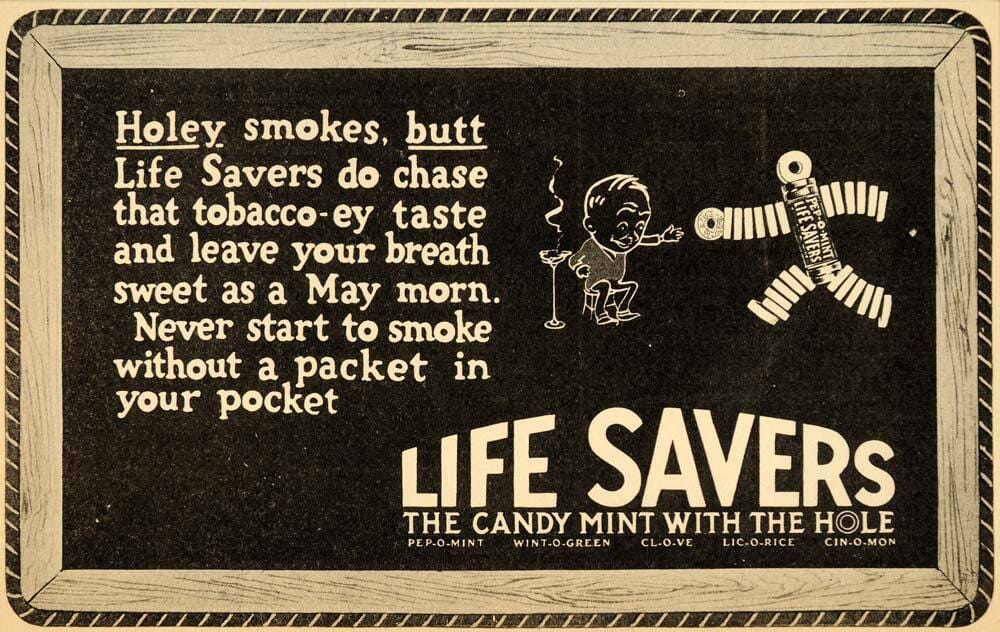

Once it had no choice, NBC moved quickly to sell off its Blue Network. It even had a name picked out: ABC, the American Broadcasting Company. In 1943 it found a buyer: Edward J. Noble, a radio station owner who’d once served in the US Department of Commerce, but who had made his fortune as head of the Life Savers candy company.

Whatever works, “baby”!

People tried to warn the righteous regulator James Fly that once the Blue Network was on its own financially, it would not be able to continue providing so much public-interest programming. “Without the profitable Red network to support it, market forces would cause the Blue to become commercial just to survive. Fly’s reformist zeal blinded him to this fact of network life,” Bergreen writes (132).

ABC was born just a few years before television really began to take off in the US. It struggled to gain a foothold and was open to try anything to survive. First it merged with United Paramount Theaters, another spin-off company created by court-ordered anti-trust divestiture. With a lot more Hollywood types in the company, ABC embraced the combination of movies, television and “entertainment” generally. It took a pitch from Walt Disney, already rejected by other networks, to invest in a new theme-park development and to air cartoons (and soon The Mickey Mouse Club). In the process of merging the film world with television, Laurence Bergreen writes, ABC accelerated the end of the live-production model that had dominated radio broadcasting.

The industry's perennial loser, ABC, now began setting precedents which all networks followed. In its desperation, the ragtag network had found the formula that was to dominate television network entertainment in the foreseeable future….Movies quickly replaced live drama as a television staple.

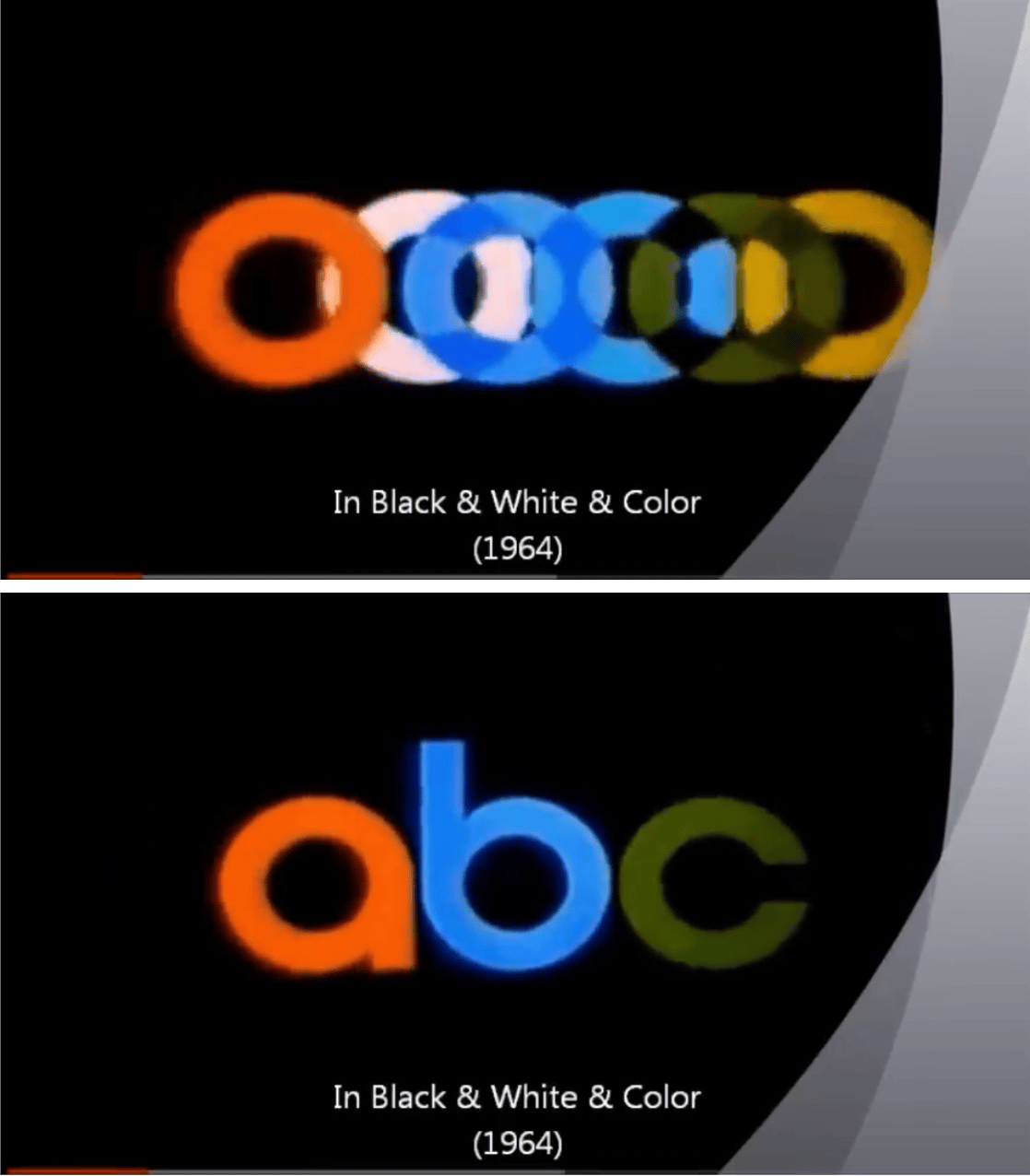

By this point, candy man Edward Noble had cashed out and moved on. But I want to believe that his Life Saver legacy lives on in the ABC logo. In the mid 1960s, it acquired its smooth, round features thanks to Paul Rand, who also designed the IBM and UPS logos, among many others. Here in this video, you can watch ABC’s lowercase letters join up from colored rings. Can you see the family resemblance?

I can find no evidence to support my theory. Thanks to Reddit, I came across a 1991 cable-access interview with designer Paul Rand. He talks about how ABC’s logo, prior to his redesign, was mocked as “The Toilet Seat.” But no mention of Life Savers at all.

What do you think?

Does the ABC logo reference Life Savers?

Whatever the truth, Paul Rand seems very wise in his dealings with corporations and their anxieties. “People will always see things,” he says. “You know, perception is reality. Reality is not reality. It’s only what people think.”

What do I think? ABC, you screwed up last week, and now you are experiencing afresh the misery of being seen. It must be even worse for a company born of a divorce, and then reborn through merger upon merger upon merger. How ironic also that the court case that led to your birth, National Broadcasting Co. v United States, is part of the precedent that now allows another activist FCC chair to threaten your affiliate stations while speaking on an unregulated rightwing podcast distributed by Cumulus Media.

On the upside, you are still young compared with your dad/stepbrother. I know you’ll do better, at the very least so you can go back to hiding. But think upon your forgotten past, ABC. Maybe, in a corner of your leveraged corporate soul, some part of you is still proud to be Blue.