The infernal feed

Spend a minute on Apple’s top podcast charts and you will see a lot of shows that arguably cause harm to this world. I’m not going to enumerate them, and you can judge the harm according to your own moral standards. On aggregate, though, it clearly seems like this corner of the audio world is a profitable place for those who traffic in misogyny and racism, quackery and conspiracy, grift and bullshit.

That’s depressing, of course — but the medium is not the message. It just shows that audio has power, and naturally, not only the virtuous want a piece of it.

I’m fond of a mordant book called The Infernal Library, which asks why so many of the 20th century’s dictators started out as wannabe writers and editors. The author, Scottish-born Texan Daniel Kalder, took it upon himself to read Hitler’s terrible tomes, Lenin’s screeds and Mussolini’s editorial diatribes as a literary genre (unaffectionately, dic lit). Kalder undertook this awful task, he says, because we need to better understand the relationship between media and monstrosity.

“Many people regard books and reading as innately positive, as if compilations of bound paper with ink on them in and of themselves represent a uniquely powerful ‘medicine for the soul,’” he writes. “However, a moment’s reflection reveals that this is not even slightly true: books and reading can also cause immense harm.”

Over the next few posts, I want to do with radio/tv/podcasting what Kalder has done with dic lit — pick apart some bad examples to better understand the foundations of their diabolical success. There are two big reasons to do this: As a listener and viewer, it’s good to know how you are being worked on. And if you are a producer, it’s good to avoid becoming a moral monster. Because the very things that make propaganda a success are temptations for us all.

Today we’ll consider the work of Soviet “Americanist” Valentin Zorin, and in particular, one film he made about my hometown.

Valentin Zorin on the levee in Dallas, 1978. The watermark is for a Russian streamer of old Soviet film and TV, “Nostalgia.”

Americanist abroad

Zorin was one of the Communist empire’s most famous news commentators, a fixture on Soviet television akin to Walter Cronkite or David Brinkley — though Zorin wasn’t an anchor. He was a foreign correspondent for long stretches in the United States, bringing his Marxist expertise on US capitalism to bear on political and social issues. He was proud of the fact that he’d interviewed (or at least interacted with) every US president from Dwight Eisenhower to George W. Bush.

I first ran across Zorin’s documentaries while working on a podcast series set in the late Cold War, and I became obsessed. Later, I convinced Harvard history professor Jill Lepore, whose show The Last Archive I edited for Pushkin Industries, to do an episode about Zorin with me. If you want a salty take on the man, I do recommend listening.

Zorin’s main series for Soviet state TV (the only kind of TV) was called America in the 70s. He and his film crew went to Chicago, Los Angeles, Pittsburgh, New York, Boston and many other cities. Most of the films that are now online are not subtitled in English (the films about New York and Boston are, kinda — translated by enthusiasts).

These films are an incredible glimpse of the US through the eyes of a professional stranger on an “unending anthropological mission,” as one scholar of his work put it to me. And all them were a huge deal when they aired in the USSR. But they are not just artifacts. How Zorin talked about the US matters still, because his analysis seem to have influenced the current leadership of Russia, including and especially, Vladimir Putin.

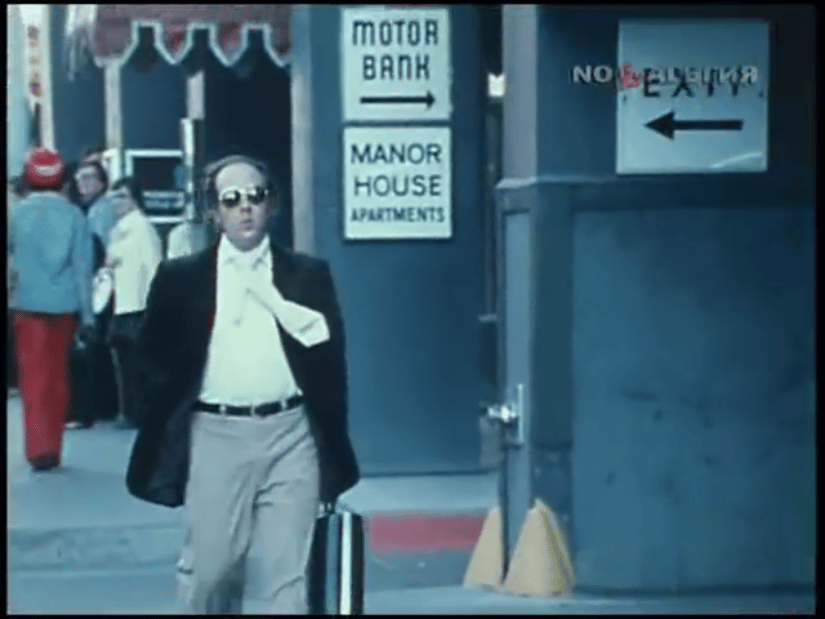

Screenshot from The Puzzles of Dallas

In 1978, Soviet TV aired Zorin’s documentary The Puzzles of Dallas. I grew up in Dallas — while Zorin was in town filming, I was probably running around the playground, pretending to have Farrah Fawcett hair.

It’s truly a Looking-Glass experience seeing my childhood realm through the eyes of a didactic Leninist. It’s also fascinating because he gets many things right — something that Jill Lepore points out about successful propaganda in general: for it to work, it must be a “cocktail of truth and lies.”

The Puzzles of Dallas is full of well-worn observations of the sort many a writer (including yours truly) have proclaimed about the town: that it worships shiny buildings and huge freeways; that it loves spectacle and bling; that it seems perpetually insecure about its status and its soul.

In the Soviet cinematic style, each one of Zorin’s points about Big D is illustrated with visual metaphors. His cameras linger on the weedy banks of the Trinity River, the ramshackle commercial strip of Black South Dallas, the shiny but incomplete Reunion Hotel still being constructed downtown. When I posted a link to the film on social media, folks in Dallas were amazed by this Russified time capsule of a city that is constantly changing its looks.

But then my astute friend, the local history blogger and archivist Paula Bosse, noticed something: not every image in The Puzzles of Dallas is actually of Dallas.

Dallas.

Not Dallas.

The first image is from South Dallas. The other, which goes by in a flash, appears to be Harlem, perhaps some unused footage from Zorin’s film Two New Yorks. Maybe it was added to make the less crowded, but very real poverty of Dallas look … poorer.

But there’s more. Zorin’s film contains a lot of footage of Dallas tycoons such as Stanley Marcus, who’s seen inspecting new fashion items at his flagship store Neiman-Marcus. And then there’s local oil billionaire H.L. Hunt. We see Hunt at home, in his office, and on the way to his office (not only did Hunt famously drive an old car, but he parked on the street to avoid paying fees at his own company’s garage).

Zorin’s footage of Hunt seemed suspect to me on several counts: not only was Hunt a rabid anti-Communist unlikely to let a Soviet film crew near him, but he’d died in 1974, three years before Zorin came to town.

Finally I figured out that Zorin lifted all this footage — as well as the scenes with Stanley Marcus and many others — from a 1968 BBC documentary called The Plutocrats: Rich, Super Rich, Texas Rich. Filmmaker Adam Curtis loves that doc and has posted several minutes of it here, and they are frame-for-frame what Zorin used to illustrate Hunt, with nary a mention of the Beeb.

Still of H.L. and Ruth Ray Hunt, from The Plutocrats

In fact, I would guess that almost a quarter of Zorin’s Dallas documentary is lifted from this already ten-year-old BBC production. How could he get away with this?

This is where you start to see the one necessary condition of the magic spell Zorin cast: Information asymmetry. Zorin knew many things his Soviet audience could not. This was long before the Internet, and besides, the USSR was an authoritarian state that restricted travel and access to outside media. Zorin could be certain that almost no one in his audience would have seen the BBC doc. And if the BBC complained, who cared?

(By the way, Zorin’s shoddy ethics extended to his film’s soundtrack which, I figured out with the help of Shazam, was supplied by Western artists who presumably never got a kopek).

Cultural learnings of America

Information asymmetry is one of the most devious tools in the propagandist toolkit, because it’s pretty subtle unless you know a lot about the topic at hand. It depends on non-acknowledment and obfuscation. Plenty of casino games are based on information asymmetry. So is espionage.

Think also about characters like Borat, Sacha Baron Cohen’s mockumentary caricature of a post-Soviet correspondent. He roams America, getting xenophobes and bigots to expose their stupidity, while spouting non sequiturs like, “I am Kazakh. I follow the Hawk.”

Cohen knows something his American victims don’t, which is that he is completely pranking them. Valentin Zorin was no Borat, but he had a similar advantage over his hosts. He knew much more about Americans than they knew (or chose to know) about him, and he gained their trust only to betray it later in ways that shocked and baffled them.

It seems from newspaper coverage that Zorin left a trail of broken hearts in his wake once his American subjects later saw or read what he said about their towns.

“I could not have put together a show that would demolish Kansas City with the meanness of spirit they did,” one of the Soviet film crew’s local guides told the New York Times after Zorin’s doc implied that native son Harry Truman built fake voter rolls with names in the local cemetery.

In Dallas, Zorin managed to get a representative of Hunt Consolidated, a company run by the descendants of H.L. Hunt, to show him around the town. This fact blew my mind when I read it, because for about 15 minutes of the film, Valentin Zorin spins an elaborate tale about the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. Behind it all, Zorin claims, was none other than Hunt himself.

The Kennedy stuff is where Zorin really starts to lose me — and it’s not because I have some secret admiration for Hunt, who was a ham-fisted propagandist himself. No, it’s just that, like everyone who grew up in Dallas, I have been overexposed to Grassy Knoll content and find it tedious (Erykah Badu excepted).

Still, here’s my attempt to summarize Zorin’s theory: He says the rising power of the “oil bloc” in the South and Southwest, as represented by Hunt, were in a power struggle with Northern industrialists represented by President Kennedy. So they decided to do away with him when he came to their home turf, thus anointing a regime friendlier to their interests in the form of Texan Lyndon Johnson. Oh, and also Hunt hired Jack Ruby to kill Lee Harvey Oswald. Obviously.

But though he says Lee Harvey Oswald’s name, Zorin never mentions Oswald’s years in the Soviet Union, or his marriage to a Soviet citizen — information you might think his viewers would find interesting. That makes it pretty hard for me to trust anything else he has to say.

Soviet storms castle

Remember how I said Zorin got a representative of the Hunt company to show him around? I’m guessing that was all so he could get this sequence: Zorin ascending the endless lawn of Mt. Vernon, the plantation replica Hunt built for himself alongside local reservoir White Rock Lake. It’s almost as if he were going to interview the powerful oilman himself, whose status as dead is somehow never mentioned.

Once news of The Puzzles of Dallas got back to Dallas, the Hunt people were of course flummoxed by what their charming Russian visitor alleged about their old boss.

“I reckon it’s fair to say he didn’t return our Texas hospitality very nicely,” spokesperson Jim Oberwetter complained to the AP in 1978. I emailed Oberwetter the archival coverage, asking if he recalled the encounter with Zorin or his Soviet crew. He wrote back that he didn’t remember any of this. But then, a lot had happened in the interim, such as him serving as US ambassador to Saudi Arabia under President George W. Bush. (I can only imagine Zorin chuckling over that development, if he knew.)

Mute on

Because Zorin’s Soviet audience was so closed off, it was rabidly curious about the outside world. That gave his documentaries an almost hypnotic power. Media historian Dina Fainberg writes that Zorin’s films were shown repeatedly on Soviet TV, but people took what they wanted from them.

For travel-starved Soviet viewers, the lens of Zorin’s camera offered a rare opportunity to see America. Watching “with the sound off ” meant that audiences enjoyed the footage from the US while tuning out Zorin’s narration, which situated the footage in the appropriate ideological context. Similarly, many readers turned to the journalists’ published long-form accounts to satisfy their curiosity about American cities, culture, and everyday life. As they read, audiences brushed off the journalists’ ideological commentary and instead scoured the texts for raw information about life in the United States.

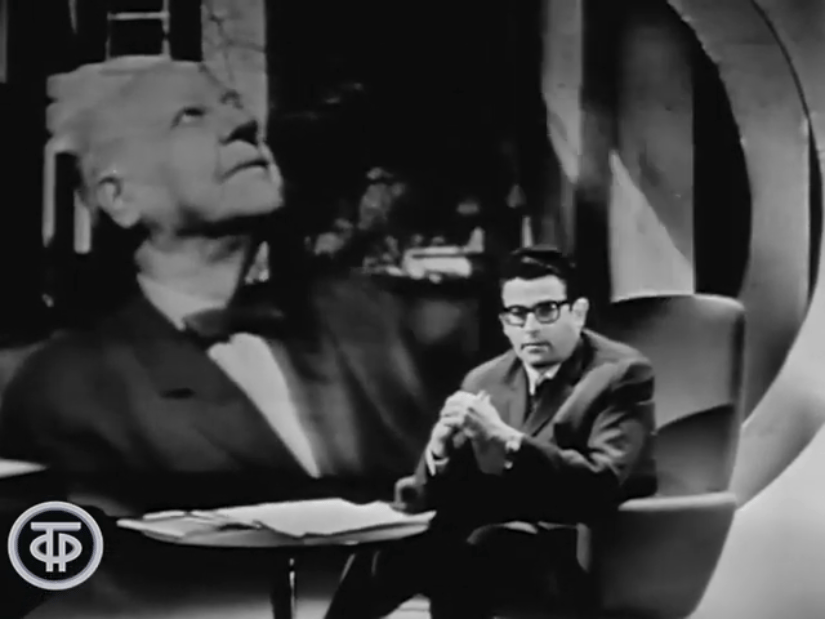

Back in 1970, long before he came to Dallas in person, a much more strident, studio-bound Zorin appeared as host of a show called Masters Without Masks, all about US capitalists and their skulduggery. And who did he unmask not once, but in at least three episodes? H.L. Hunt. And what did he use to illustrate Hunt’s perfidies? Uncredited footage from the 1968 BBC film The Plutocrats.

The Puzzles of Dallas was not a new exposé on Zorin’s part — it was a rerun.

Valentin Zorin in 1970, with BBC footage of Hunt in background.

Dina Fainberg got to interview Zorin a few years before he died in 2016 at the age of 92. And she told me he insisted that he felt real affection for America. She heard that same insistence from many of the old Soviet correspondents she met.

“I think they genuinely liked American people. They were critical towards the United States as a system, as a political system, as a political culture. And they saw through all sorts of things. But they liked Americans, and empathized with them, and made an effort to understand them,” she said.

I believe her, and I know it took incredible survival instincts to make it as a Soviet journalist in the West. There were countless things Zorin couldn’t say on air that maybe he wanted to say — but it also seems true that the more stuff he didn’t say, the more comfortable he got just saying versions of what he’d already said. In that way, he resembles all too many other “news commentators” today, who don’t think it’s necessary to explain how they formed their opinions.

All the ethical practices they teach in journalism school are designed to counteract the temptations of information asymmetry. Stuff like: make sure assertions of fact have multiple sources — and cite them if they’re really important. Issue corrections when you get something wrong (by the way, I will do this here!). Above all, whenever possible, give the people you are talking about the chance to speak for themselves.

The only Dallas residents we hear from in Zorin’s doc are those interviewed by the BBC, plus a few students on the campus of SMU who were studying Russian. Unfortunately, their Russian is not great, and it feels like this segment was included for laughs. But if Soviet viewers indeed had the sound off, they might have missed that. All they would have noticed was a faraway eruption of something without a name in Russian: Farrah Fawcett hair.

Я не знаю, y’all.

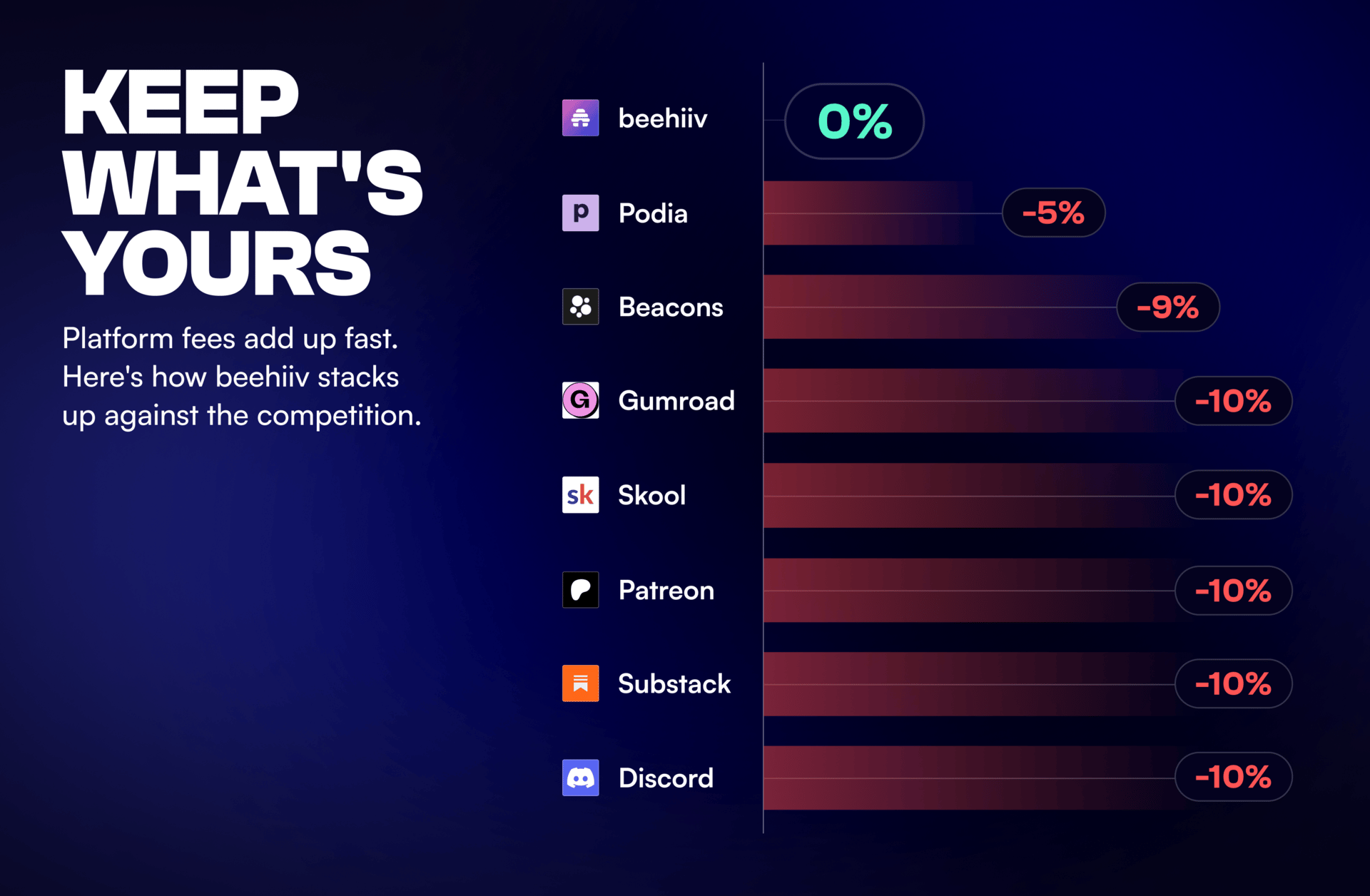

Can this idea actually make money?

The fastest way to find out is simple — launch a newsletter and website in minutes, then turn what you know into something people can buy.

With beehiiv’s Digital Product Suite, your expertise becomes real products: a short guide, a playbook, a set of templates, or limited access to your time. No friction, and no code required. Just create, price it, and share it with your audience.

And unlike other platforms that quietly take 5–10% of every sale, beehiiv takes 0%. What you earn is yours to keep.

For a limited time, get 30% off your first 3 months on beehiiv with code PRODUCT30.