I am just back from New York, where I caught an excellent production of Letters Live, a charity event in which a secret roster of performers (on our night, Nathan Lane, Laura Linney, Sarah Cooper, and David Byrne, among others) read from an eclectic selection of letters: bizarre customer service complaints, bawdy notes, poignant elegies to the dead. I recommend this show if it comes to your continent! Tickets are relatively affordable, especially compared with the other production in town I would have attended, had I chosen the career of “heiress.” Instead, I took inspiration from the letters to pen the following note.

Dear George,

Of course, we have never met. You are a famous actor, currently headlining Good Night and Good Luck, one of the highest-grossing Broadway shows of all time, based on a 20-year-old movie you co-wrote about famous newsman Edward R. Murrow. In a couple of days — June 7, 2025 — you’ll be live-streaming your next-to-last performance on CNN. So your movie about television has been adapted to a play that will be on TV: you are truly “platform agnostic,” as they say.

I am a less agnostic audio story editor. But I’m also someone who is fascinated, as you seem to be, with the history of broadcasting and its relevance today. Hence my humble newsletter Continuous Wave — which does not charge admission prices of up to $849 but does cover some of the same ground as your Murrow project. I was inspired to rewatch your 2005 film. Back then, David Strathairn was the actor playing Murrow, going eyebrow-to-eyebrow against anti-communist Senator and general terror-of-the-nation Joseph R. McCarthy. You played the role of Murrow’s lead producer, Fred Friendly.

An editor’s editor

So why am I writing to you, a person of infinitely more fame, money, and cheek-bone definition than I will ever know? It’s because I noticed something while watching your movie and the series of broadcasts it’s based upon. Everyone who’s interviewed you or reviewed your Broadway production has noted that it ends with the fat finger of irony pointed at the present. Ed Murrow and his team are meant to be avatars for journalistic courage, especially for the way they challenged, via their weekly CBS newsmagazine See It Now, the never-ending Red Scare that consumed Washington.

You told Maureen Dowd this play “feels more like it’s about truth, not just the press. Facts matter.”

Indeed they do! Even now, in this era of semantic misery, most Americans say they want facts from the media and they consider facts to be a signifier of “news,” as opposed to “commentary” or “entertainment.” The problem now, of course, is any agreed definition of what constitutes “truth” and “facts.” Unfortunately, that comes down to trust.

Let me put it more clearly, George Clooney. You may feel that Good Night and Good Luck is about stuff like truth and facts — but really, it is about whom we choose to trust and why. Even you, a famous person and Democratic donor in rooms with Presidents, cannot see the whole world with your own eyes. You need witnesses to report back. We need the media, and we need to trust what the media tells us, for this “facts” business to function.

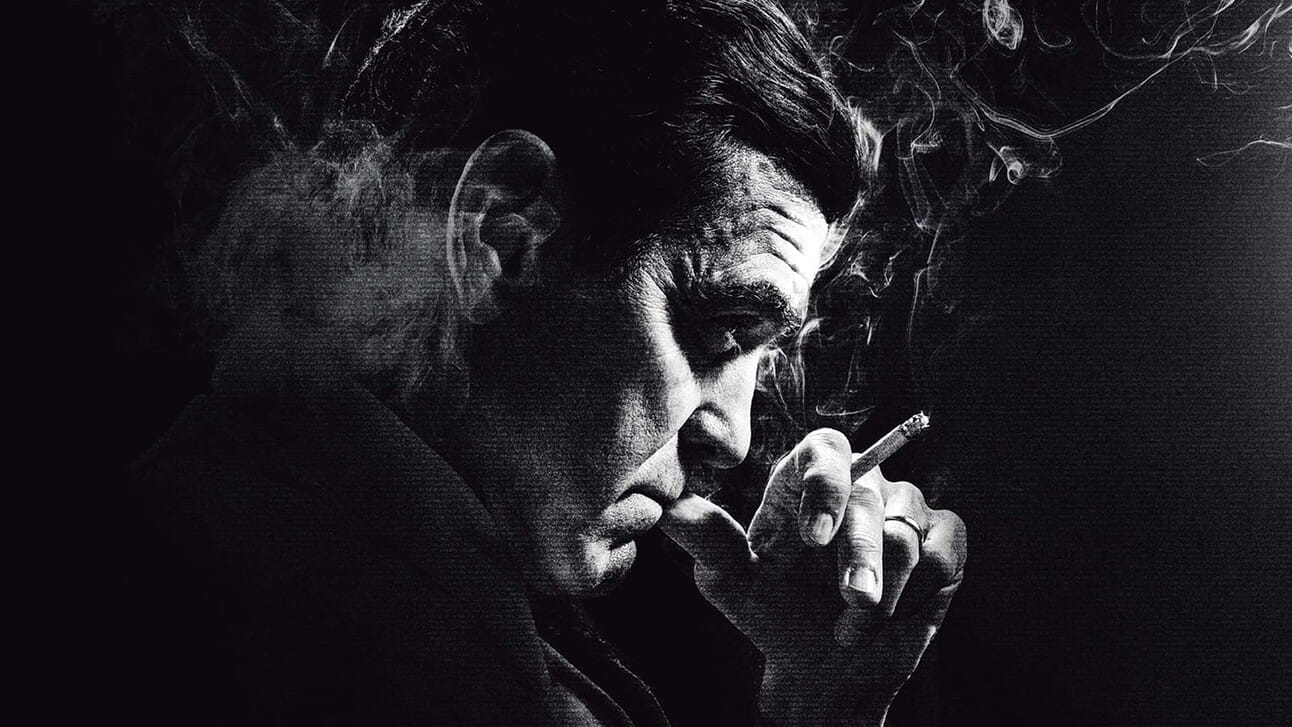

The actual Edward R. Murrow in 1954 (TIME/LIFE)

To my mind, a lot of this comes down to the editorial process, which is just a fancy phrase for handling decisions at any media outlet, regardless of size. How do we balance the constraints of deadlines, ethics, verification, and our treatment of sources with the need to generate income, and to fit material into established formats? Consistent editorial judgment builds trust over time. The editorial process is what stands between fact-based media and other media that act simply as a series of pipes to squirt random rhetoric, bullshit and/or vibes across the land.

Of course I would say that as an editor. But I suspect you’d agree because your dad was a trusted local news anchor for decades. So, just to edit your words a little, I think you mean to say that your production is about the importance of the editorial process. After all, Edward Murrow himself was called the “editor” in the intro to See It Now. (He was also called “distinguished reporter and news analyst” because they liked to lay it on thick.)

The actuality game

Here’s something else interesting from that intro. It called the show “a document for television, based on the week’s news and told through the actual voices and faces that made the news.”

That word “actual” is a big clue to the innovation that Murrow and Friendly were bringing to broadcasting, and it was so important that the introduction uses the word twice. It goes on: “Now speaking to you from the actual control room of Studio 41 is the editor of See It Now, Edward R. Murrow.” At which point Murrow swivels to the camera, cigarette in hand, to start the program. He’s in the actual control room so he can call up field reports and interviews on the monitors to his left. These monitors act as props — the field reports quickly materialize and fill our whole screen. But Murrow has evoked the reportage through this little magic trick. In his cramped control room, surrounded by knobs and cameras, he is both the master of ceremonies and the guy who makes sense of everything at the end with a little homily.

Murrow delivered a banger at the end of A Report on Senator Joseph R. McCarthy, the famous March 9, 1954 broadcast you spend the most time re-enacting. Quoth Murrow: McCarthy “didn't create this situation of fear. He merely exploited it, and rather successfully. Cassius was right. ‘The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, but in ourselves.’ Good night, and good luck.”

Now, this particular program of Murrow’s was a bit unusual in that it didn’t have any reports from the field. It consisted mostly of clips from speeches and hearings featuring Senator McCarthy railing against this or that menace, a stray cowlick escaping his comb-over to flop against his wide forehead.

In both your versions of Good Night and Good Luck, McCarthy appears in archival tape, just as he did in the original Murrow broadcast. (On Broadway, this fact has caused a lot of complaints from spectators who wished McCarthy had been portrayed by an actor).

Your keeping McCarthy contained within tape highlights the very game that Murrow and Friendly established with their show. It was a game McCarthy was almost certainly bound to lose. That’s because inside Studio 41, there were no live “guests” — I mean, where would they even fit in there? Other people were always on tape.

There’s even a moment a couple of minutes into his famous 1954 program when Murrow plays a reel-to-reel tape of McCarthy’s voice, in order to bring us words from a speech that wasn’t filmed.

I’m telling you, George, this moment reveals everything. Edward Murrow is hosting live. The Senator is 100% pre-recorded and thus already contained. Immediately after the broadcast, CBS offered to foot the bill for McCarthy to film a half-hour rebuttal, and he took them up on it. The fool. In his film, which aired a month later, McCarthy comes across as unhinged, apoplectic and worst of all, boring. The following week, Murrow was able to swat aside all of the Senator’s allegations that the newsman had somehow once been a communist.

But what if instead McCarthy had said to CBS, “No, I will not film my rebuttal. I demand that famed correspondent Edward Murrow come to my Senate chambers with a live hook-up so I can berate him with innuendo about a pinko past”? The whole thing would likely have gone quite differently.

Why? For that, we need a little radio-history flashback {cue rippling FX…}

The broadcast hierarchy

You and many other distinguished white guys of Hollywood could all get roles if you chose to dramatize the National Conferences on Radio Telephony starting in 1922. From what I’ve read, these meetings created a juncture in history that changed everything. Not long after the first high-level meeting between the nascent broadcasting industry and its regulators, the government declared that radio licenses for stations with a decent (“Class B”) broadcast footprint would need to be live. No recorded material would be allowed on their air — at the time, that meant records or player pianos. Whether this regulation was made to advantage certain business interests, to repress jazz, to further police the radio spectrum, it’s not super clear.

Anyway, the government ban on recordings soon fell away — but in the meantime, liveness became the business model of the new radio networks, NBC and CBS. In fact, both officially banned recorded material from their air until 1949. In terms of radio’s development worldwide, this was an unusual stance. As I write here, your man Ed Murrow chafed against the ban while reporting from London and was once dinged by his CBS bosses for including a bit of tape in a report during the Blitz.

Ed Murrow’s fame came from being a live radio correspondent. His co-producer Fred Friendly was more of what you might call a tape guy. The two first worked together in 1947, when Murrow was brought in to record narration for an album project Friendly was producing. It was a compilation of famous speeches and historical moments — recordings of the very type that reporters like Murrow had been told not to use on radio. The album was called I Can Hear It Now and was a smash success. Its format, a pastiche of pre-recorded elements stitched together by a host, became the basis of See It Now, which itself is the basis of most TV news magazines and newscasts today.

By the 1950s, it had become much easier to record and edit media because of advances in film and magnetic tape technology (thanks, Nazis!). But Murrow and Friendly would never, even with their generous budget and perfectionist tendencies, consider pre-taping their entire show. Sure, some elements were pre-recorded, but at the center of it all, Murrow always spoke live to his audience. He knew instinctively, as newscasters have before and since, that liveness is where the power of broadcasting lies.

You know it too, George. You’re live-streaming your play on CNN, not uploading it to YouTube. Perhaps you hope this live event will mean that when, at the end, your production points the fat finger of irony at the present, it will provoke insights in the viewer. Give us courage by example to speak out for facts, truth, something like that.

Signal lost

Murrow and Friendly created an incredible container to make sense of the world via sound and visuals. It is worthwhile to praise their courage, innovation and precision under very difficult circumstances. And it is natural, especially for a TV anchorman’s son, to want us to reassemble that container. But unfortunately, it had a fatal flaw in its center that was bound to shatter it eventually. That flaw was, and is, the addictive effect of live broadcasting on its audience.

David Strathairn, Good Night and Good Luck, 2005.

No matter how much reasoned discourse and great factual prose Ed Murrow banged out on his typewriter, broadcasting’s power had, from the beginning, been built on spectacle. It hooked its audience with live broadcasts of boxing matches and election returns, or wall-to-wall coverage of disasters like bombing campaigns and kidnappings. Its power grows every time the three-point shot touches the net as the buzzer sounds, or an actor flubs their lines on SNL. It’s embedded in every sports bet we might just win, and every car chase we cannot stop watching from the helicopter above.

Perhaps it was inevitable that a politician, already a creature of television, would figure out how to carry the lure of spectacle with him wherever he went, to make it the ultimate point of every public appearance, whether that appearance consists of nonsense or insults or merely swaying on stage. A leader whose staff reportedly wonders how to produce his daily briefs in the style of Fox News. A public figure who sues the CBS show 60 Minutes, a direct descendant of See It Now, for causing him “anguish” simply by the act of editing an interview with his opponent.

Could Murrow and Friendly contain and shame such a figure with video and audio clips from their cool lair in Studio 41? No, they could not — and that is his entire reason for being. He has absorbed the lessons of live spectacle — how it’s conditioned an American public for a century — into his very cells. And now has unleashed that power back on the machine that built it. If your intent on CNN is to cure us of the thrall of spectacle with yet another one, I am not sure it will have much effect. Unless, that is, you go rogue.

So here is my impertinent request: toss that cigarette aside, break character and tell us the one truth that matters now: there is nothing “authentic” about live broadcasting. You have known since childhood that liveness is yet another editorial choice, simply one that’s better at hiding its work. Do people not know that most live coverage requires an expensive system of planning and coordination? Do they not see the control room? Even POTUS, for all his bluster, has to be wheeled into place at the appointed time, in front of the appointed cameras, for his “spontaneity” to work. And someone has to make the call whether or not to run the feed, and for how long.

If you’re really inspired, take the audience back further. Tell us about how broadcasting first developed to help ships communicate on the icy seas, so they were not isolated in danger. And how perhaps rescue is what we really crave from broadcasting, not more spectacle. We want reassurance that someone is out there to hear our distress calls. That someone will respond when we cry out like children in the night.

Maybe the cure is not, in fact, Ed Murrow at all. It’s Ross. Have you considered running that guy for public office?

Anyway, break a leg on Saturday. I’ll be watching. Remember: the fault is not in our stars, but in ourselves. Good luck, good night, and burn it all down.

Yours truly,

Julia

George Clooney on set at the Winter Garden Theatre (Emilio Madrid)

P.S. Here’s more info on how to catch the CNN livestream, 7pm EST on June 7th, 2025.

Fact-based news without bias awaits. Make 1440 your choice today.

Overwhelmed by biased news? Cut through the clutter and get straight facts with your daily 1440 digest. From politics to sports, join millions who start their day informed.