Note from Julia: I’ve said it before — US network radio in the 1920s and 1930s was an absolute embarrassment when it came to race. Not only did early radio deploy crude ethnic stereotypes — with popular shows like Amos’n’Andy built around the “racial ventriloquy” of white men depicting Black characters — but it was almost impossible for actual Black people to get on network air as themselves, or Black writers to get dramatic scripts past gatekeepers.

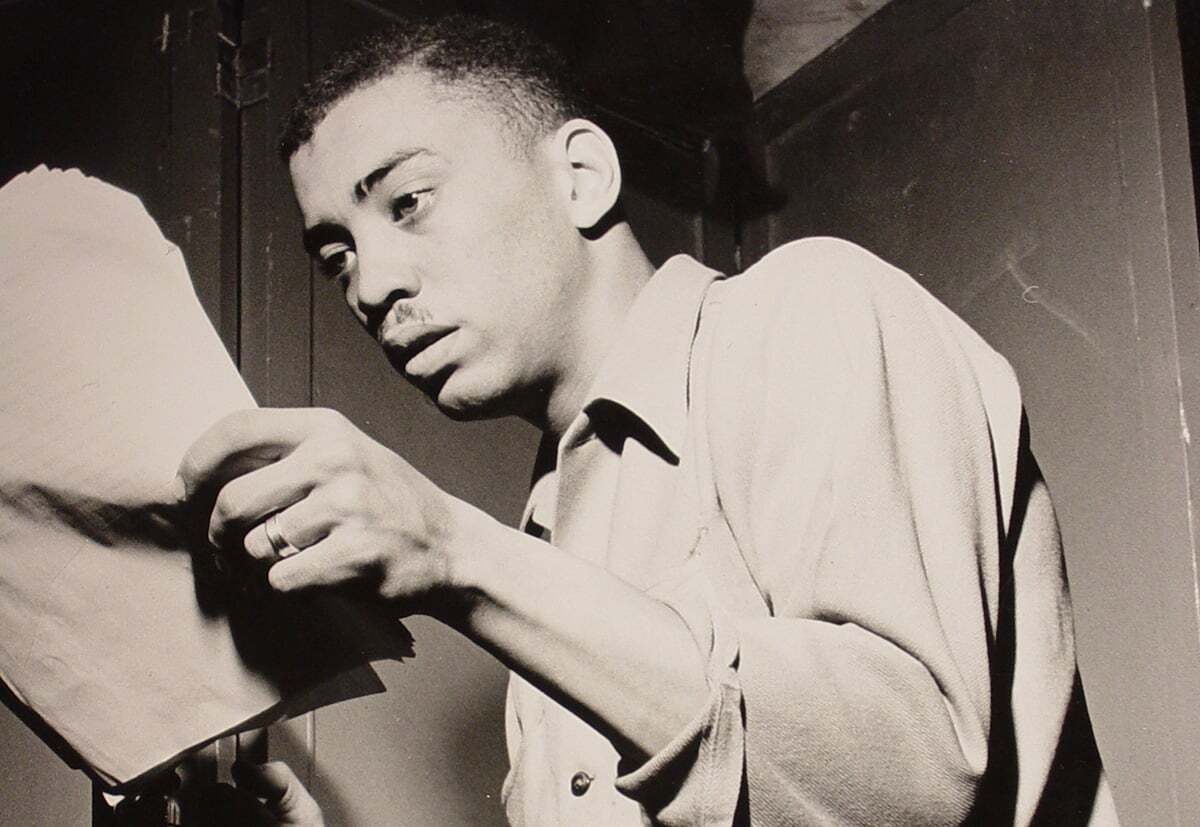

That started to change with the onset of US involvement in World War II, as the government, which needed enlistment and buy-in from Black communities, asked radio to open its doors to more voices and points of view. From this opening came a new generation of Black radio actors and writers. One of the best was Richard Durham, a journalist with the Chicago Defender who in 1948 started the history series Destination Freedom on Chicago’s NBC powerhouse affiliate WMAQ (ironically, the same station where Amos’n’Andy got its start).

Howard University professor Sonja D. Williams has written a fascinating biography of Richard Durham called Word Warrior: Richard Durham, Radio, and Freedom. Williams is also a Peabody-award-winning audio producer, and it was in the course of researching the Smithsonian’s documentary series Black Radio: Telling It Like It Was that she first encountered Durham’s work. “I was struck by this series’ lyricism, dramatic flair, and fiery rhetoric,” she writes.

Today, with Williams’ permission, we’re bringing you the story of Destination Freedom, an excerpt from Word Warrior. After this, I hope that if you haven’t already, you’ll go read the whole book. Here’s Sonja Williams:

Freedom

Richard Durham surrounded himself with giants.

Harriet Tubman. Benjamin Banneker. Katherine Dunham. Toussaint L’Ouverture. Black leaders like these spoke to him, hour after hour, as he sifted through the mounds of materials that Vivian G. Harsh, head of the Hall Branch Library, and her staff provided. Sitting in the library’s airy special collections reading room, with its dark oak floors and pale green walls, Durham read historical documents about a potpourri of Negro history makers. He learned about their triumphs. Their failures. Their idiosyncrasies. He then decided how to best shape the dramas documenting their lives within Destination Freedom’s half-hour timeframe.

Durham varied his storytelling approach, alternating between straightforward dramatic narratives and more whimsical or comical takes. Whatever the form, Durham created eloquent, politically outspoken scripts. Destination Freedom’s multiracial cast and crew then transformed those scripts into the aural equivalent of a page-turning novel.

Never circumspect about his intentions, Durham told an interviewer during the series’ run that “the job cut out for writers, actors and directors working with Negro material” called for breaking through stereotypes, shattering “the conventions and traditions which have prevented us from dramatizing the infinite store of material from the history and current struggles for freedom.” Such struggles defined what Durham called “the truly universal people” — individuals whose experiences held “the key to the essential meaning of life for men and women of our day.”

In Durham’s presentation of progressive blacks “as heroes fighting white supremacy,” scholar Judith E. Smith called Destination Freedom a “powerful expression of racially inclusive universalism.” Smith believed that Durham “reversed” Hollywood stereotypes by demonstrating that nonwhite protagonists, perceived to be “different” because of their race, were actually just like everyone else.

Universalism was one of Durham’s abiding philosophies. “I think the Afro-American represents that particular microcosm of the entire world,” Durham said years later. “And by using that particular microcosm you can reveal the human condition of the main body of people of the world.” In Durham’s opinion, oppression combined with poverty, inadequate education, and insufficient healthcare adversely affected most of the world’s population. Therefore, he believed that an American Negro’s sharecropping experience “is instantly recognizable to 500,000,000 Chinese people who have undergone the same experiences under imperialism for 300 years. A Negro character confused by the caste system in the land of his birth, is instantly identifiable to 450,000,000 Indians in Asia [or] 150,000,000 Africans in Africa.” The same connection, Durham said, could be made with Malaysians in Burma, with Jewish people struggling to create the new nation of Israel in 1948, and “with the millions of Europeans and white Americans who also want to uproot poverty and prejudice.” In addition, Durham believed that women “of all races and creeds in their upward swing towards a real emancipation, find it natural to identify their striving with the direction and emotional realism in Negro life today.”

Destination Freedom’s protagonists stood up for their rights while championing equality and justice for their fellow citizens. Yet historian J. Fred MacDonald contended that Durham’s characters, “were never able to forget the fragile quality of their triumphs… Durham poignantly illustrated that all blacks must be prepared to encounter the interference of race prejudice in any career.” For example, despite singer/actress Lena Horne’s considerable fame, a Southern restaurant refused to serve her because of her race. And women’s suffrage activist Mary Church Terrell was forcibly ejected from a public bus in the nation’s capital because she refused to move to the rear where blacks were relegated to sit based on Jim Crow dictates. According to director Homer Heck, “There was a certain sameness to the point of view” in Destination Freedom’s episodes. “The details of the stories were different of course, but I remember the whole experience with considerable pleasure. The Harriet Tubman script was one that comes to mind quickly.”

In “Railway to Freedom,” Durham’s Tubman character narrates her own story. At the beginning of the script, Harriet Tubman is a young slave, growing “wild like a weed” on a Maryland plantation. One day a fellow slave runs past her, trying to escape from the plantation. Tubman blocks their owner’s attempt to catch the fleeing slave. The owner threatens to hit her with the heavy iron bar he’s holding if she doesn’t move.

Durham’s Harriet states: “I was afraid, but I wouldn’t move. I wouldn’t move! I saw him lift the iron bar. Then his hand struck down!” Tubman collapses. Ethereal sound effects indicate her semi-conscious thoughts. “The earth moved and rockets burst in my head,” Tubman says. Durham returns often to this earth/rocket metaphor, using it to represent the painful headaches, seizures, and loss of consciousness Tubman endures for the rest of her life because of her owner’s blow.

Once Tubman emerges from her wound-induced coma, she fervently desires freedom. “There are two things I have a right to — liberty or death,” she declares. “One or the other I mean to have. I shall fight for my liberty.” Thenceforth, Harriet Tubman becomes fascinated with the Underground Railroad, a clandestine network of secular and religious organizations and individuals — black and white — who serve as the railway’s conductors or agents. They secretly provide food, shelter, or financial assistance to escaping slaves — the railroad’s passengers.

Tubman eventually rides the Underground Railroad to freedom. However, she soon realizes that she wants family members and other slaves to taste the sweetness of liberty. Tubman becomes an Underground Railroad conductor, and her numerous liberation trips back into and out of the South are rife with danger. Tubman and her passengers could be caught and dragged back into slavery at any turn. While the exact number of slaves Tubman spirited away is in dispute, she courageously led many of her people to freedom.

A couple of weeks after “Railway to Freedom” aired on Independence Day 1948, Durham wanted to bring Nat Turner’s story to the airwaves. Turner, a Virginia-based slave, led a violent revolt in August 1831. But Durham indicated that NBC officials “rejected out of hand” this suggestion. They questioned how Durham would deal with the fact that Turner’s rebellion caused the deaths of at least fifty-three white slave owners and their families. Durham compared Turner’s tale to that of Spartacus, the former soldier and slave who organized thousands of enslaved citizens and led an uprising against the Roman Empire. “How many slaveholders did Spartacus kill?” Durham rhetorically asked. “I don’t know, but [his actions] added to the freedom of the world.” Durham’s argument didn’t sway WMAQ executives.

Instead, Durham turned to the story of Denmark Vesey, a former slave who masterminded a revolt nine years before Nat Turner. Vesey’s 1822 slave revolt in South Carolina reportedly involved about nine thousand conspirators. Although Vesey’s uprising was foiled before it gained traction, his disciplined actions frightened slaveholders. They realized that Negroes were capable of taking whatever steps they felt necessary to obtain freedom. “The organization of [Vesey’s rebellion] had taken a number of years,” Durham explained. “And because the subsequent trial went on so long, there was quite a bit of material as to how it was organized.”

In order for a drama to be compelling, Durham believed that its hero needed to possess attributes the average listener also desired. “One of those attributes is courage,” Durham said. In spite of the real possibility of being thrust back into the prison of slavery, Denmark Vesey refused to move north to a more welcoming environment after paying for his freedom with money he won in a lottery. He courageously stayed in the South, inspiring his people to tear down a system that oppressed them.

In this episode, a deep-voiced narrator leads listeners through Vesey’s evolution. Durham’s script starts with his main character’s post-revolt criminal trial.

They say slaveholder’s court was crowded that day in Charleston. They say the culprit was caught in the act — had conceded the crime. They say all was over but the hanging, and soon the masters could sleep, could rest.

The script then flashes back to how Vesey wins his freedom and subsequently recruits followers. One supporter is a black woman who sells cherries in the town’s marketplace. She agrees to alert the conspirators if danger approaches. When the militia swoops in to crush the revolt, the woman hawks the agreed upon signal, “Blood Red Cherries.” She is killed, and Vesey is captured. Durham’s script ends where it began, at Vesey’s trial for treachery against the state of South Carolina. After the judge castigates the former slave for his crimes, Denmark Vesey responds with a statement that is stunning in its militancy — especially its last line — for radio of the 1940s:

Denmark: You speak of my “crimes.” I feel no guilt. I felt to be idle while other men fought to be free was a crime. I was not idle. Others talked. I acted. I’d act again!

Crowd: (Slight murmurs of unrest. “Hang him,” etc.)

Judge: (Gravel raps.) Order! Order! Is that all you can say to explain your treachery?

Denmark: (Thoughtfully.) No. My treachery began when I read the Declaration of Independence . . . it said “All men are created equal.” It grew when I read that black Crispus Attucks died to help the colonies be free. Did he die just to free white men or all men? Then I read what Ben Franklin, Tom Paine, LaFayette and Jefferson had said and their words warmed my blood. They wanted their revolution to make all men free and equal. They stopped with some men free and some men slaves. I took up where they left off. (Slower.) I found my price when I was a slave...I paid it. If my life is the price I pay to be free…take it. I’ll pay it. Until all men are free, the revolution goes on!

This statement constitutes “one of the most damning critiques of racial abuse ever heard on U.S. radio,” historian J. Fred MacDonald wrote. Certainly, Durham’s Denmark Vesey was unlike any black man normally heard on a medium where comic and subservient Negro characters ruled the day. Such characters included Rochester, played by actor Eddie Anderson on the popular Jack Benny Show, and Eddie Green on Duffy’s Tavern. The black protagonists on the still popular Amos ’n’ Andy Show continued to be played by their white creators, Freeman Gosden and Charles Correll.

So why did WMAQ and NBC allow Destination Freedom’s progressive sentiments and rebellious Negro characters on the air? One explanation may be that Destination Freedom could be heard only in Chicago. NBC officials claimed that Southern affiliates would bristle at its content and refuse to air it. Realistically, an affiliate station near Durham’s Mississippi birthplace or in South Carolina would have strenuously objected to the series’ dramatizations.

Radio networks treated shows about racial issues like a “tale of caution and restriction,” historian Barbara Savage asserted. The networks feared that programs about race would alienate listeners and damage their ability to attract and retain advertisers. Yet more liberal approaches to the race question seemed to emerge in the post–World War II era, especially “after President Harry Truman’s embrace of the rhetoric of racial equality,” and after protests by black Americans “pushed the issue onto the public airwaves,” Savage suggested. […]

Durham would later complain that WMAQ shut Negroes out of salaried positions. Durham essentially remained a freelancer, working full-time hours for low contractual pay during Destination Freedom’s run. When he approached [WMAQ programming manager] Homer Heck about this, Heck allegedly told Durham that Heck “didn’t see that changing during his time.” Actors Oscar Brown, Jr. and Fred Pinkard complained about not being allowed to audition for better-paying roles on shows broadcast nationwide by NBC. According to Brown, Heck claimed that Southern affiliate stations would object to having Negro actors in the cast. Oscar replied, “It’s radio. They would never see us or know we were colored.”

Reprinted from Word Warrior: Richard Durham, Radio, and Freedom, copyright 2015, University of Illinois Press, with permission of the author.

Sonja Williams talks about her research at the Library of Congress here.

Thank you so much to Professor Williams for sharing her excellent work with us. Do check out her series Black Radio as well, now in podcast form via Selects.