Radio’s power couple

Why do so many people think podcast and radio stories are just magically spoken, not written and edited? I asked that recently in this post, but the question has been on my mind for a long time — and not only because it’s integral to my livelihood (no writing = no editors). Like many before me, I find it a strange paradox that the very presence of writing has been obfuscated in what is a word-based medium. Now that I’ve been Reading a Shit-Ton™ about radio’s past, I better understand at least one origin of the no-writer fallacy in the US context. And that origin story has a name: the Hummerts.

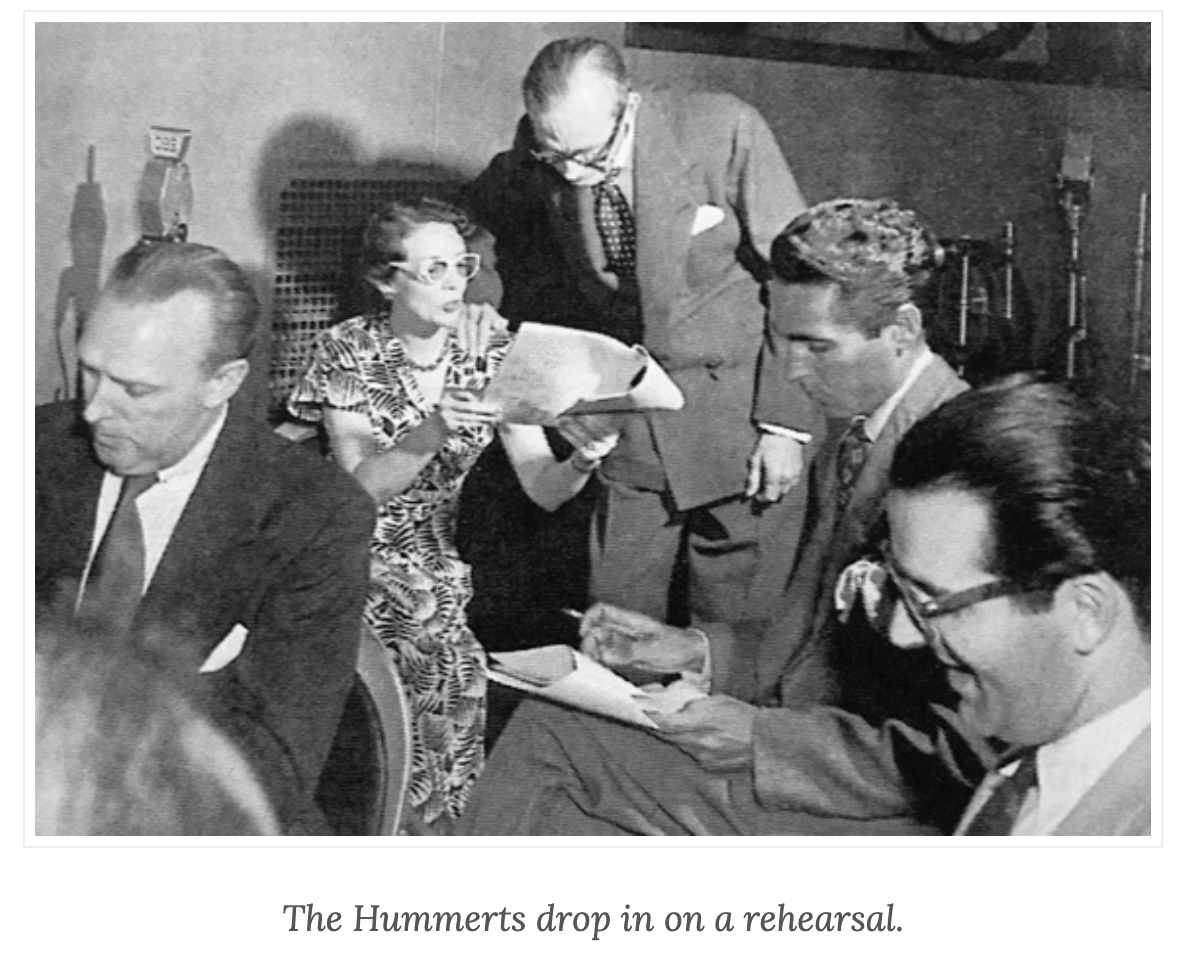

Frank and Anne Hummert were the power couple behind dozens and dozens of hit shows — as well as many flops — on commercial network radio from the 1930s-1950s. They ran an incredible ad agency/production assembly-line that churned out hours and hours of programming: musical reviews, true-crime mystery plays, comedies, children’s programming, and above all, daytime serials. Also known as soap operas. The Hummerts couldn’t write all that themselves, so who did? You’d have to work hard to find out.

The moguls of melodrama

Perhaps like many of you, I’ve had the experience of watching TV soaps while home sick from school, or during a desultory summer, when I’d try to follow the lurid yet brightly-lit melodramatic turns of Days of Our Lives or General Hospital. But radio soaps were different from their TV successors. First of all, they were generally short: 15 minutes, of which two to five minutes were taken up by advertising and plot recaps. Second of all, they were sparsely produced and pretty boring, not sexy or dramatic. Something was always about to happen in a radio soap opera — but in each individual episode, very little did happen, apart from talking. The Hummerts didn’t want much to happen, because that would introduce complications to the plot and the production process. They weren’t out to win the Nobel Prize for literature. They came from the advertising world, and their goal was to sell their clients’ stuff. When a show’s formula for storytelling-plus-sales got consistent results, they would just keep it running until the sponsorship ended.

By the 1940s, this twosome controlled four-and-a-half hours of national weekday broadcast schedules. Their features reportedly spawned more than five million pieces of correspondence annually from steadfast fans. Simultaneously they brought in more than half of the national radio chains’ advertising revenues generated during the daylight hours. The couple broadcast 18 quarter-hour serials five times weekly, a total of 90 original episodes for 52 weeks per year, with none of those ever repeated…. Simply put, the Hummerts were indisputably the moguls of melodrama.

Many other radio producers also did well in the soap-sponsorship domain (check out the new podcast series Audio Maverick about one of them). But the Hummerts’ shop beat out everyone else in terms of sheer quantity and longevity. Network executives tried to wine and dine them — always tricky since they barely seemed to eat. The few colleagues who got invited to the Hummerts’ Fifth Avenue apartment recalled being served a dinner of canned soup, followed up by canned peaches.

The longest-running Hummert serial featured the never-ending travails of a Hollywood costume designer, Helen Trent, as she sought true love. Helen Trent was played by three different actresses across 7,222 episodes. Helen Trent was always 35 years old. She remained 35 years old for 27 years.

This kind of storytelling paradox fascinated and repulsed critics. “There is nothing in the daytime serial for the occasional listener, except mystification; and a careful observer, listening every day for weeks, is astounded at the slow pace of events, wondering how anyone can listen so long to so little,” marveled writer and producer Gilbert Seldes. He goes on:

In one serial it took a man a full installment to decide that as the last house on the block was numbered 1676 and the first house, two blocks farther, was 1800, the place he was looking for, number 1700, must be the big house occupying the intervening block; and this was the fourth of five installments in which the man set out to call at the house in order to see his estranged wife; having discovered the house on Thursday, he spent all but the last minute of Friday in conversation with a friend, giving him a résumé of the events that had caused the separation; in the final minute he saw her step into a car and drive away — providing the necessary week-end “suspense.”

Seldes’s attitude towards soaps was basically “you gotta hand it to them.” But many, many people hated these programs with a passion. Radio soap-opera discourse very much resembles “brain rot” fears about social media today — that the content is vapid yet addictive, that it preys on the vulnerable, that it isolates us and makes us stupider. Everyone took a swing at radio soaps: James Thurber, Ed Murrow, and the Canadian radio playwright Merrill Denison. In his book-length screed Generation of Vipers, Philip Wylie connected soap operas vaguely to Goebbels’ “mass-stamping of the public psyche,” writing that “a whole nation of people lives in eternal fugue and never has to deal for one second with itself or its own problems.”

And the haters weren’t just men, who could be accused of not comprehending the home-bound frustrations of the soaps’ target audience: housewives who maybe just wanted a few minutes alone with their gal-pal Helen Trent, the ageless costume designer. In 1940, several women in Westchester County, NY, started an anti-soap campaign called “I’m Not Listening,” urging other women to turn off their radios until daytime programming got less tedious and formulaic. The New York Times was on it, of course. And it covered the networks’ panicked response, which was to hire social scientists to discover that women who listened to soap operas were not brain-dead after all.

Whew, another moral panic is laid to rest! (New York Times, October 25, 1942)

What radio writers wanted from soap operas was different from what the critics wanted. The writers wanted to get paid something close to the going industry rate for their scripts. In 1938, the Hummerts paid $25 per finished script. A decade later, they paid $35. By that point, in the late 1940s, scriptwriters on other dramatic series could earn $1000 a week, often more. Even with the Hummerts’ expectations that their writers turn out 15-25 scripts/week for multiple series, their writers still earned far less than they could from other shops. It didn’t help that the Hummerts were by now fabulously wealthy, owning not only their apartment on Fifth Avenue, but a mansion in Connecticut staffed (allegedly) by Japanese servants.

The Hummerts had become notorious in the radio world as eccentric, controlling, reclusive and cheap. If you served merely as a scriptwriter for their company Air Features, you never met them in person. Contract writers received plot synopses in the mail that they were expected to fill in, episode by episode, with intro copy and dialogue. These writers were not allowed to suggest new ideas or character development. The Hummerts liked to rotate scribes around so they’d never get too attached to a particular show. Working on a Hummert production was a purely transactional grind, for which the writers would never get credit in print or on air.

But Cynthia Meyers points out in her great book A Word from Our Sponsor (Fordham University Press, 2014), the Hummerts applied advertising, not literary, logic to the work they demanded. Before Frank Hummert ever came up with the idea of a daytime serial to sell soap, he’d become famous as a “reason why” copywriter — someone who came up with simple, memorable slogans that could be repeated often, and that eventually got people to buy things. He was a Don Draper precursor, albeit one who (allegedly) subsisted mainly on Shredded Wheat and water.

The point of reason-why copy is to get everything else out of the way of its suggestive powers. “Critics often mocked the repetitive, slow, over-enunciated, and humorless quality of the Hummert serials, but these features were intentional applications of the reason-why advertising strategy,” Meyers writes (114).

As for on-air credit, the radio writer and media historian Erik Barnouw recalled ad-agency types claiming that this would spoil the “illusion” that the characters in serialized dramas were “real” (see The Golden Web, 109). But such a condescending and weird assertion about listener gullibility was never attributed to the Hummerts, as far as I can tell.

Some soap operas started off right away (after the sponsor ad of course) with a writing credit. But as for the Hummerts, I’m with Meyers, who speculates that they resisted on-air credits because of the world they came from: “In advertising, copywriters did not sign their work; they were craftsmen, not artists, working for the advertiser’s benefit, not their own.” (121)

The Hummerts were arguably the most successful producers in US commercial radio history. And they considered their radio programs to be extended ads powered by story engines. The word-fuel for those stories was mined from the brains of interchangeable, low-paid copywriters. Yes, those writers might have gotten into radio because they were inspired by the likes of Orson Welles or Norman Corwin, but if they took Hummert money, they had to accept the ultimate aim of their job: to get Proctor & Gamble and other products into shopping carts. The Hummerts’ assembly-line advertising mindset about authorship went on to influence television writing and, I’d argue, the subconscious minds of American listeners and viewers. Do we know who wrote the copy on this box of detergent? No! So why should we care who wrote the dramatic stuff sandwiched between ads for detergent either?

But the world turns…

Network radio had become one of those industries that, like Hollywood, drew theater- and literature-minded creatives into a tense relationship with a system that wanted their talents, but not their ideals. The writers were not without power, however. In the late 1930s, many joined a new subdivision of the Authors Guild called the Radio Writers Guild. Under the National Labor Relations Act (RIP?), the Radio Writers Guild gained the right to bargain collectively on behalf of its members. By 1948, they were demanding that major ad agencies in the radio space, including and especially the Hummerts, sign a “letter of adherence” to higher minimum pay rates, as well as on-air credit for scriptwriters. If not, the Guild members said, they’d strike against the offending agencies and production houses.

But then, at the eleventh hour, the Hummerts pulled a move so surprising, so unexpected, that one of their daytime serials could have milked the drama for months, if not years.

What did they do? For that, you’ll have to tune in for the next post’s installment of… I don’t know — what should we call this?